Chapter 9. Data-Flow Analysis

ABSTRACT

Compilers analyze the IR form of the program in order to identify opportunities where the code can be improved and to prove the safety and profitability of transformations that might improve that code. Data-flow analysis is the classic technique for compile-time program analysis. It allows the compiler to reason about the runtime flow of values in the program.

This chapter explores iterative data-flow analysis, based on a simple fixed-point algorithm. From basic data-flow analysis, it builds up to construction of static single-assignment (ssa) form, illustrates the use of ssa form, and introduces interprocedural analysis.

KEYWORDS Data-Flow Analysis, Dominance, Static Single-Assignment Form, Constant Propagation

9.1 Introduction

As we saw in Chapter , optimization is the process of analyzing a program and transforming it in ways that improve its runtime behavior. Before the compiler can improve the code, it must locate points in the program where changing the code is likely to provide improvement, and it must prove that changing the code at those points is safe. Both of these tasks require a deeper understanding of the code than the compiler's front end typically derives. To gather the information needed to find opportunities for optimization and to justify those optimizations, compilers use some form of static analysis.

In general, static analysis involves compile-time reasoning about the runtime flow of values. This chapter explores techniques that compilers use to analyze programs in support of optimization.

Conceptual Roadmap

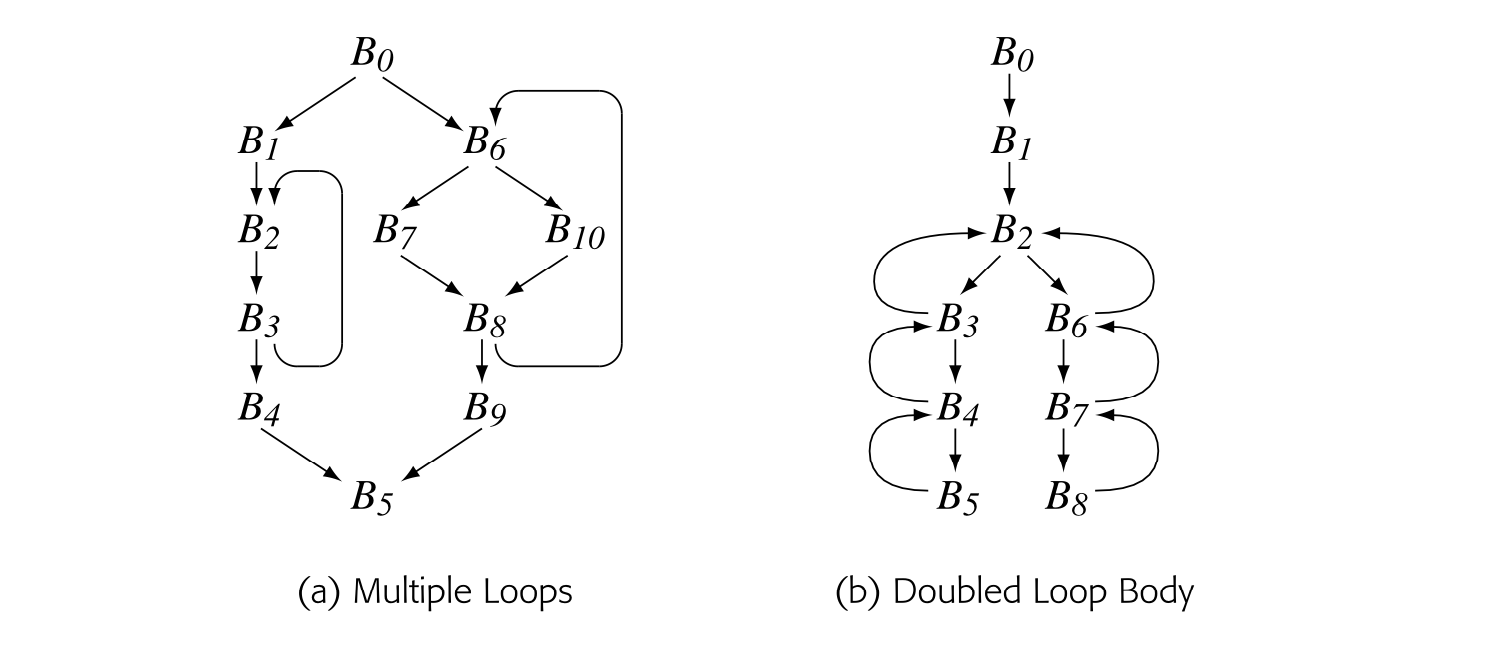

Compilers use static analysis to determine where optimizing transformations can be safely and profitably applied. In Chapter , we saw that optimizations operate on different scopes, from local to interprocedural. Ingeneral, a transformation needs analytical information that covers at least as large a scope as the transformation; that is, a local optimization needs at least local information, while a whole-procedure, or global, optimization needs global information.

Static analysis generally begins with control-flow analysis; the compiler builds a graph that represents the flow of control within the code. Next, the compiler analyzes the details of how values flow through the code. It uses the resulting information to find opportunities for improvement and to prove the safety of transformations. Data-flow analysis was developed to answer these questions.

Static single-assignment (SSA) form is an intermediate representation that unifies the results of control-flow and data-flow analysis in a single sparse data structure. It has proven useful in both analysis and transformation and has become a standard ir used in both research and production compilers.

Overview

Chapter 8 introduced the subject of analysis and transformation of programs by examining local methods, regional methods, global methods, and interprocedural methods. Value numbering is algorithmically simple, even though it achieves complex effects; it finds redundant expressions, simplifies code based on algebraic identities and zero, and propagates known constant values. By contrast, finding an uninitialized variable is conceptually simple, but it requires the compiler to analyze the entire procedure to track definitions and uses.

Join point In a CFG, a join point is a node that has multiple predecessors.

The difference in complexity between these two problems lies in the kinds of control flows that they encounter. Local and superlocal value numbering deal with subsets of the control-flow graph (CFG) that form trees (see Sections 8.4.1 and 8.5.1). To analyze the entire procedure, the compiler must reason about the full cfg, including cycles and join points, which both complicate analysis. In general, methods that only handle acyclic subsets of the cfg are amenable to online solutions, while those that deal with cycles in the cfg require offline solutions--the entire analysis must complete before rewriting can begin.

Static analysis analysis performed at compile time or link time

Dynamic analysis analysis performed at runtime, perhaps in a JIT or specialized self-modifying code

Static analysis, or compile-time analysis, is a collection of techniques that compilers use to prove the safety and profitability of a potential transformation. Static analysis over single blocks or trees of blocks is typically straightforward. This chapter focuses on global analysis, where the cfg can contain both cycles and join points. It mentions several problems in interprocedural analysis; these problems operate over the program's call graph or some related graph.

In simple cases, static analysis can produce precise results--the compiler can know exactly what will happen when the code executes. If the compiler can derive precise information, it might determine that the code evaluates to a known constant value and replace the runtime evaluation of an expression or function with an immediate load of the result. On the other hand, if the code reads values from any external source, involves even modest amounts of control flow, or encounters any ambiguous memory references, such as pointers, array references, or call-by-reference parameters, then static analysis becomes much harder and the results of the analysis are less precise.

This chapter begins with classic problems in data-flow analysis. We focus on an iterative algorithm for solving these problems because it is simple, robust, and easy to understand. Section 9.3 presents an algorithm for constructing SSA form for a procedure. The construction relies heavily on results from data-flow analysis. The advanced topics section explores the notion of flow-graph reducibility, presents a data structure that leads to a faster version of the dominator calculation, and provides an introduction to interprocedural data-flow analysis.

A Few Words About Time

The compiler analyzes the program to determine where it can safely apply transformations to improve the program. This static analysis either proves facts about the runtime flow of control and the runtime flow of values, or it approximates those facts. The analysis, however, takes place at compile time. In a classical ahead-of-time compiler, analysis occurs before any code runs.

Some systems employ compilation techniques at runtime, typically in the context of a just-in-time (JIT) compiler (see Chapter 14). With a JIT, the analysis and transformation both take place during runtime, so the cost of optimization counts against the program's runtime. Those costs are incurred on every execution of the program.

9.2 Iterative Data-Flow Analysis

Forward problem a problem in which the facts at a node n are computed based on the facts known for n’s CFG predecessors

Backward problem a problem in which the facts at a node n are computed based on the facts known for n’s CFG successors.

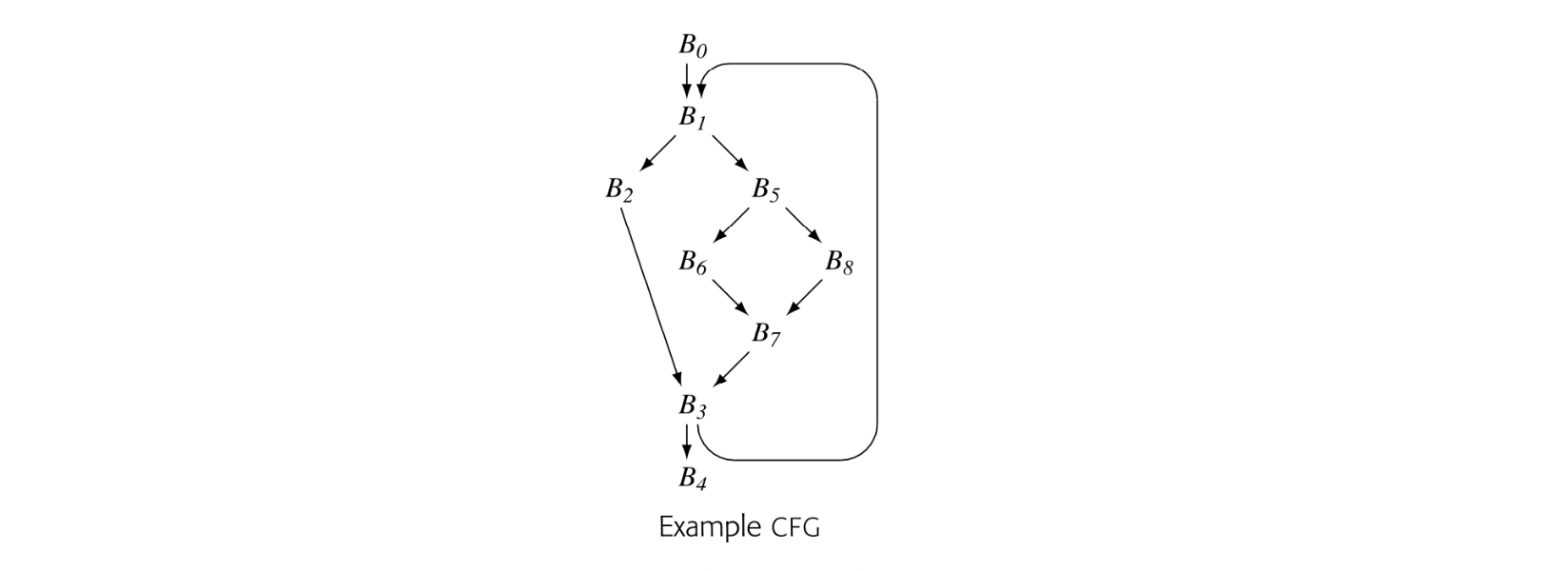

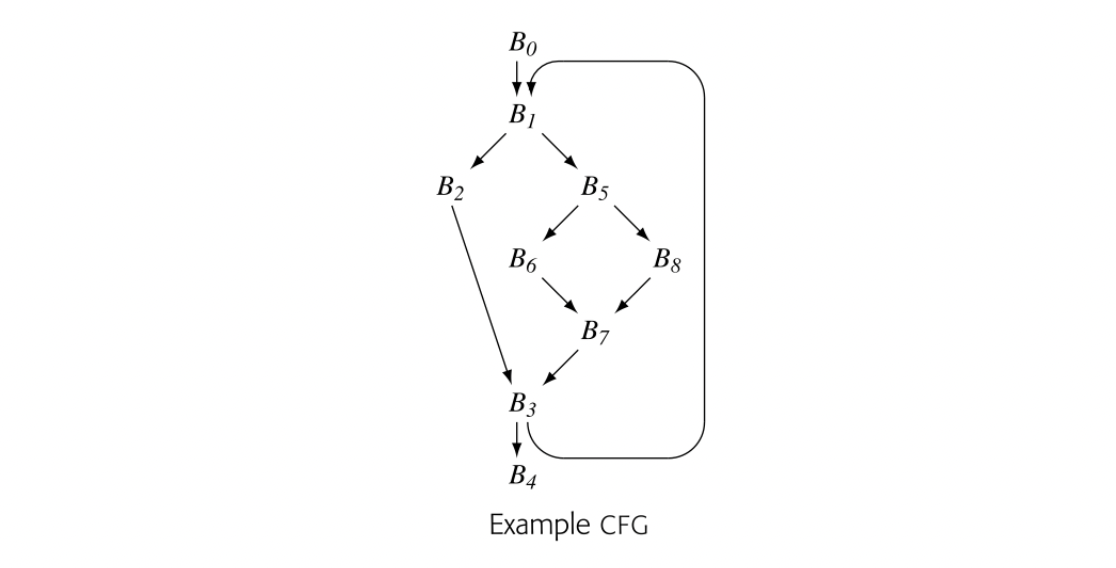

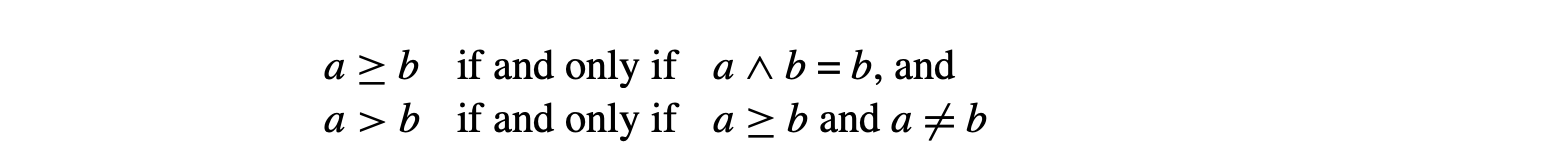

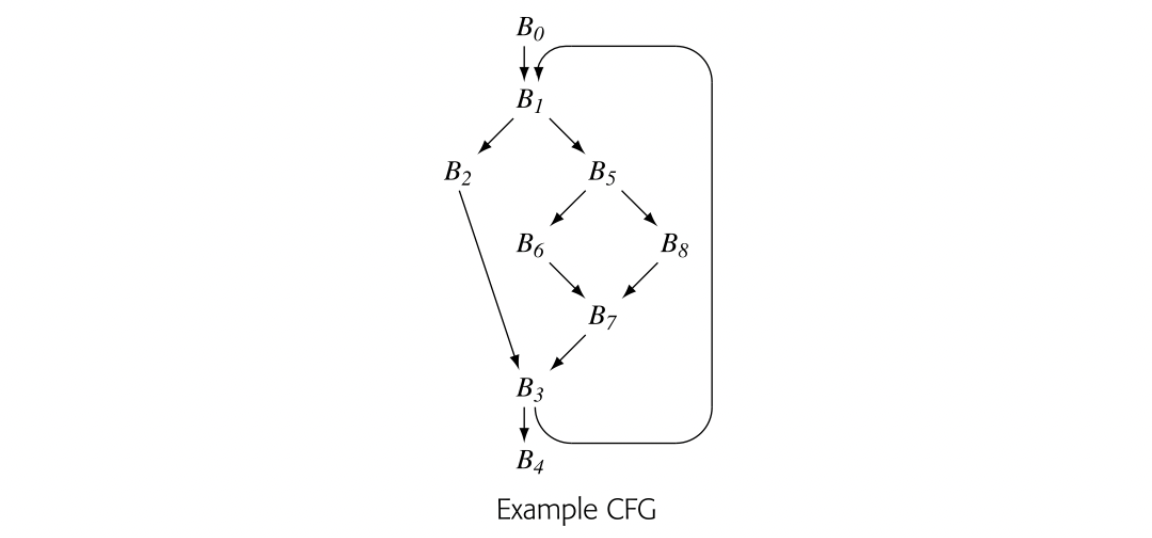

Compilers use data-flow analysis, a set of techniques for compile-time reasoning about the runtime flow of values, to locate opportunities for optimization and to prove the safety of specific transformations. As we saw with live analysis in Section 8.6.1, problems in data-flow analysis take the form of a set of simultaneous equations defined over sets associated with the nodes and edges of a graph that represents the code being analyzed. Live analysis is formulated as a global data-flow problem that operates on the control-flow graph (CFG) of a procedure. In this section, we will explore global data-flow problems and their solutions in greater depth. We will focus on one specific solution technique: an iterative fixed-point algorithm. It has the advantages of simplicity, speed, and robustness. We will first examine a simple forward data-flow problem, dominators in a flow graph. For a more complex example, we will return to the computation of LiveOut sets, a backward data-flow problem.

9.2.1 Dominance

Dominance In a flow graph with entry node , node dominates node , written , if and only if lies on all paths from to . By definition, .

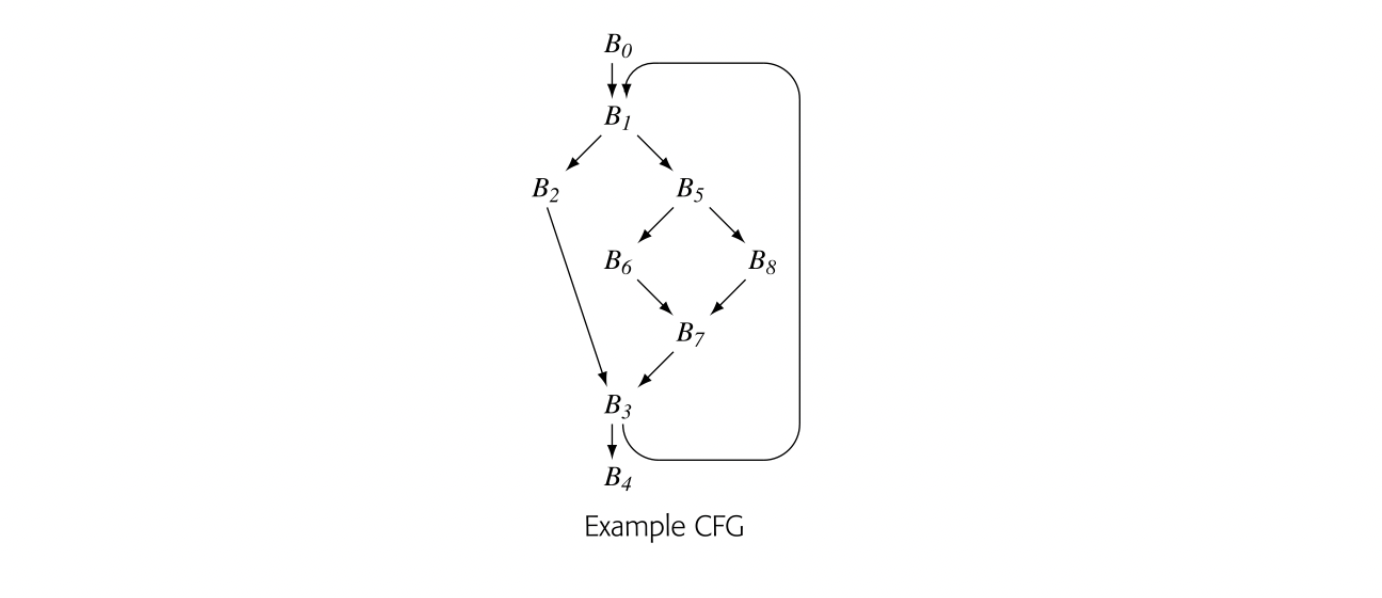

Many optimization techniques must reason about the structural properties of the underlying code and its CFG. A key tool that compilers use to reason about the shape and structure of the CFG is the notion of dominance. Compilers use dominance to identify loops and to understand code placement. Dominance plays a key role in the construction of SSA form.

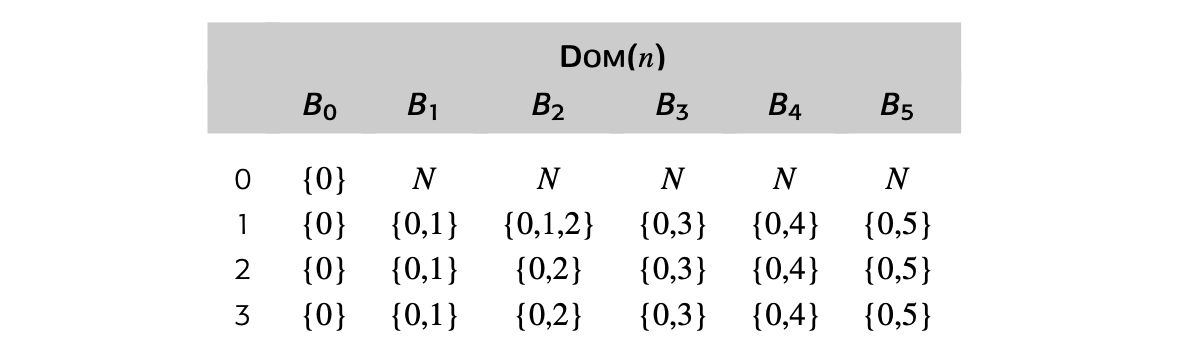

Many algorithms have been proposed to compute dominance information. This section presents a simple data-flow problem that annotates each CFG node with a set Dom(). A node's Dom set contains the names of all the nodes that dominate .

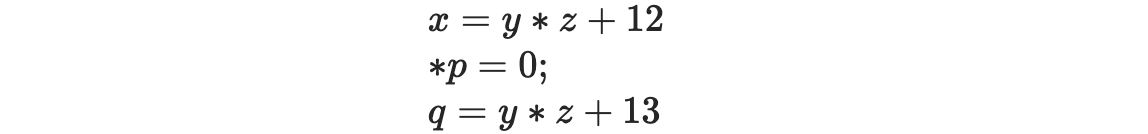

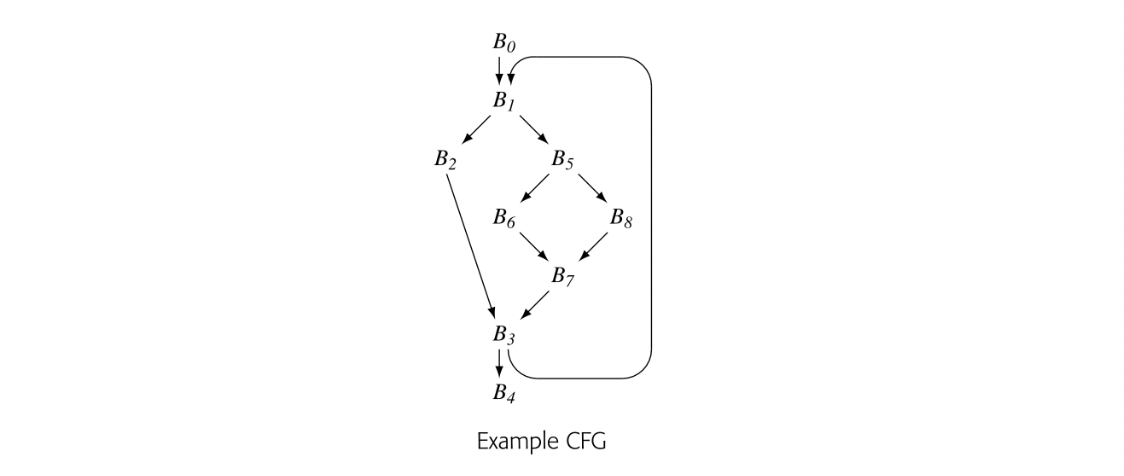

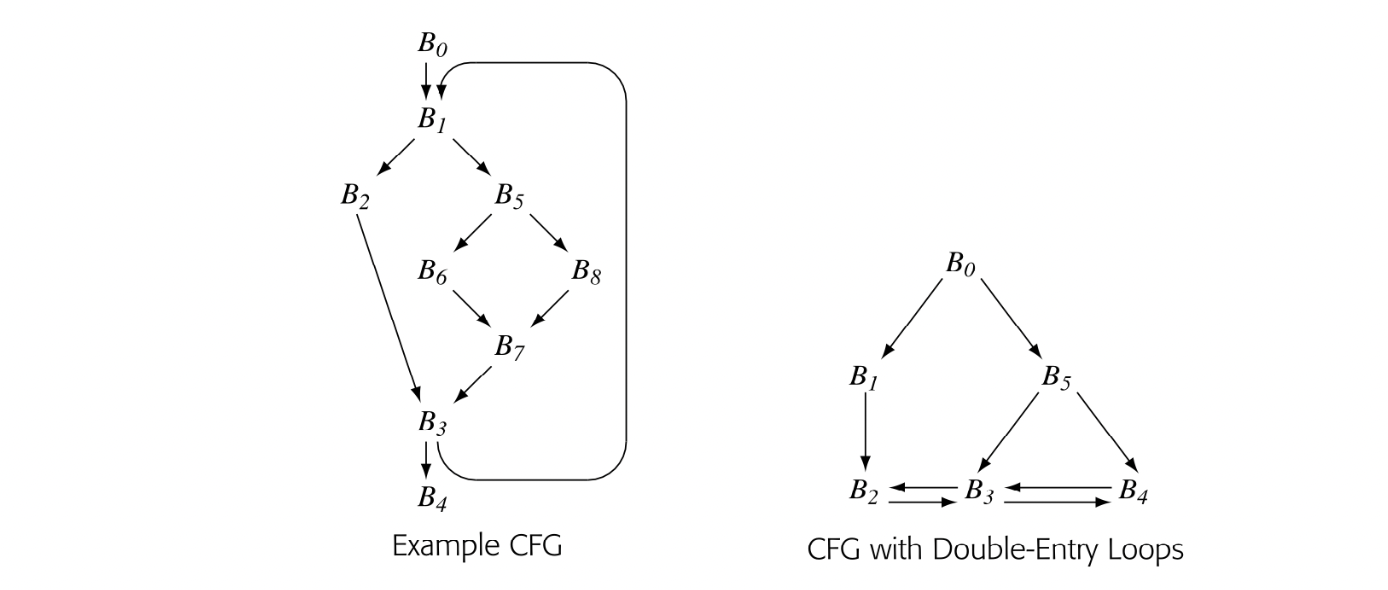

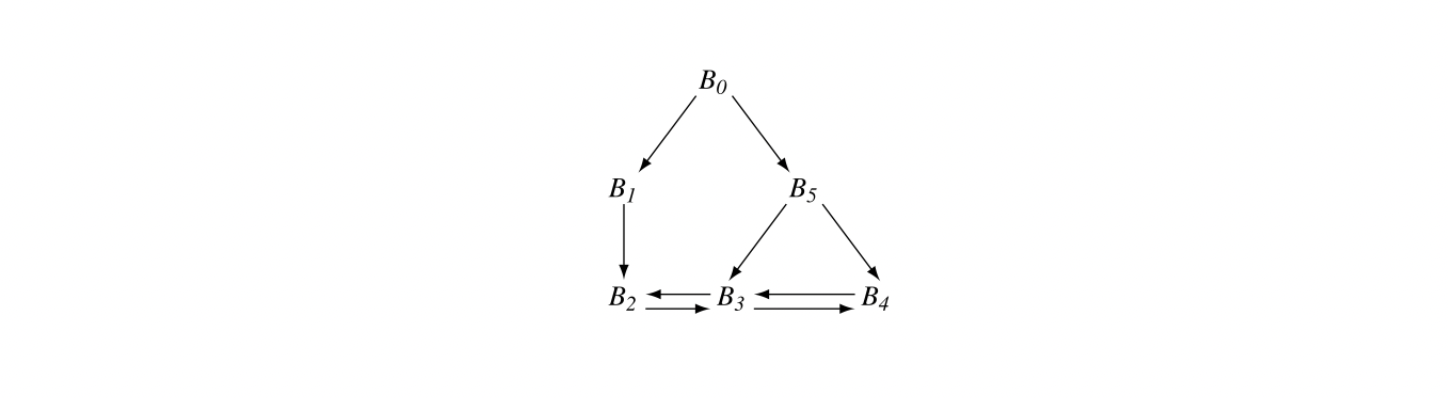

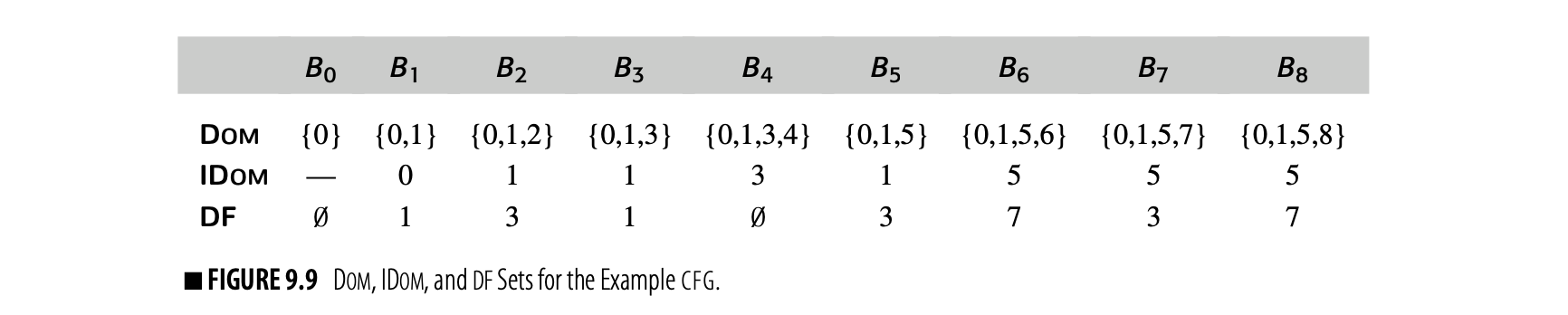

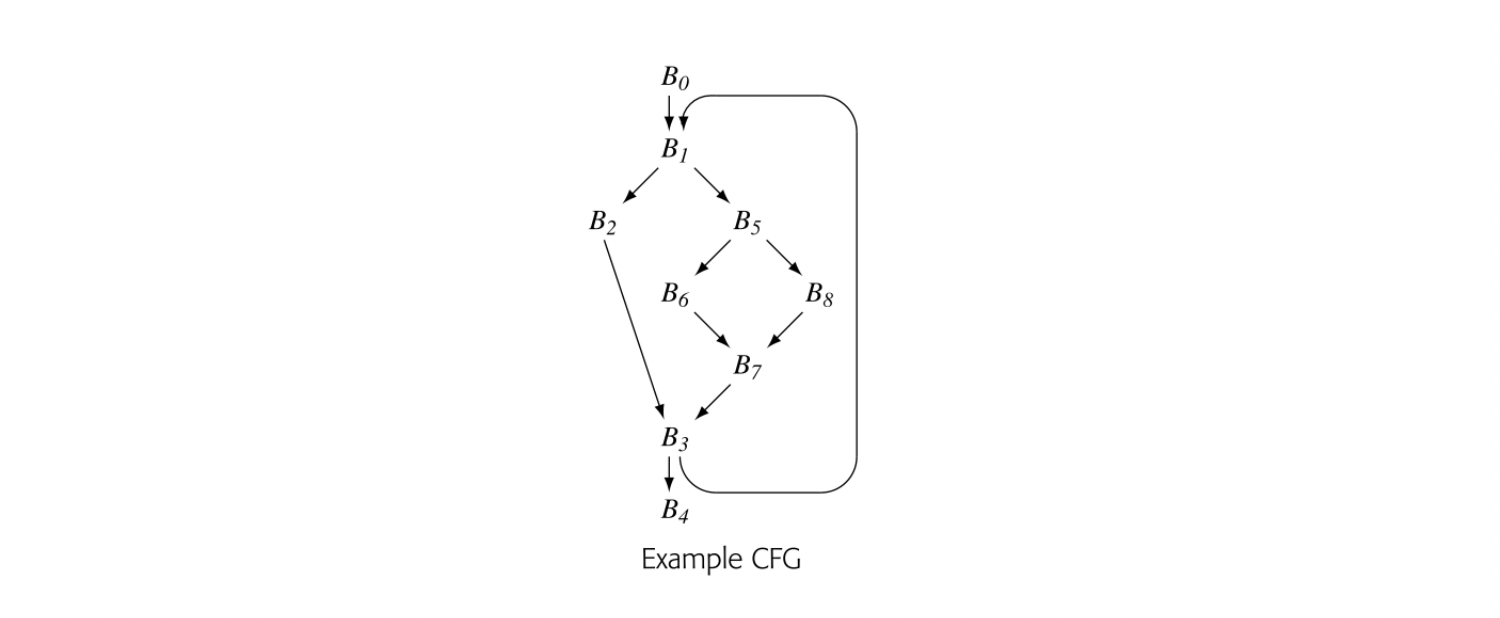

To make the notion of dominance concrete, consider node in the CFG shown in the margin. Every path from the entry node, , to includes , , , and , so Dom() is . The table in the margin shows all of the Dom sets for the CFG.

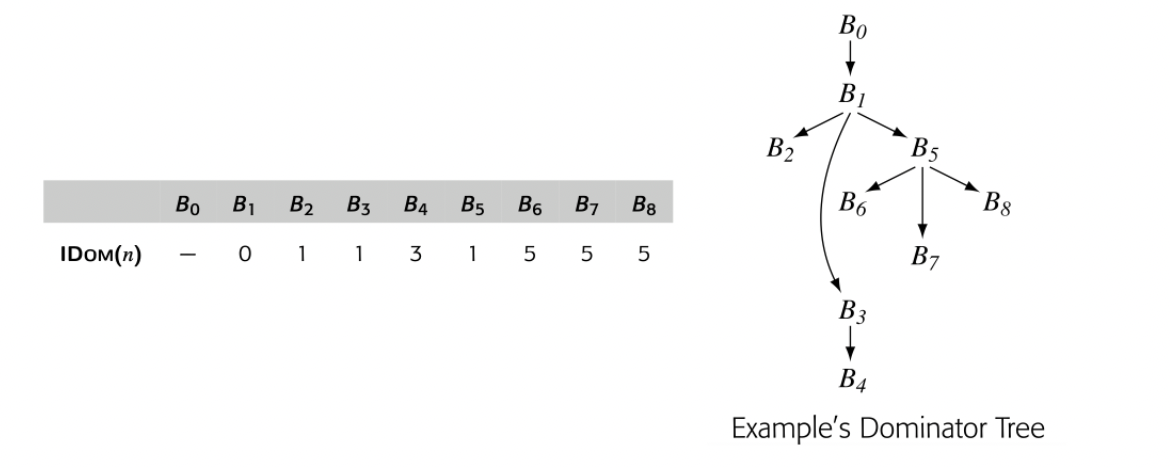

For any CFG node , one , , will be closer to in the CFG than any other , . That node, , is the immediate dominator of , denoted IDom(). By definition, a flow graph's entry node has no immediate dominator.

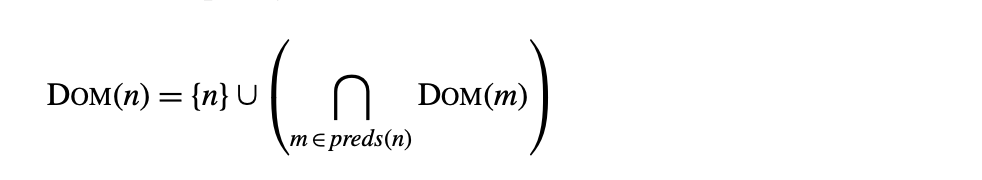

The following equations both define the Dom sets and form the basis of a method for computing them:

To provide initial values, the compiler sets:

To provide initial values, the compiler sets:

where is the set of all nodes in the CFG. Given an arbitrary flow graph--that is, a directed graph with a single entry and a single exit--the equationsspecify the Dom set for each node. At each join point in the CFG, the equations compute the intersection of the Dom sets along each entering path. Because they specify Dom() as a function of 's predecessors, denoted , information flows forward along edges in the CFG. Thus, the equations create a forward data-flow problem.

where is the set of all nodes in the CFG. Given an arbitrary flow graph--that is, a directed graph with a single entry and a single exit--the equationsspecify the Dom set for each node. At each join point in the CFG, the equations compute the intersection of the Dom sets along each entering path. Because they specify Dom() as a function of 's predecessors, denoted , information flows forward along edges in the CFG. Thus, the equations create a forward data-flow problem.

To solve the equations, the compiler can use the same three-step process used for live analysis in Section 8.6.1. It must (1) build a CFG, (2) gather initial information for each block, and (3) solve the equations to produce the Dom sets for each block. For Dom, step 2 is trivial; the computation only needs to know the node numbers.

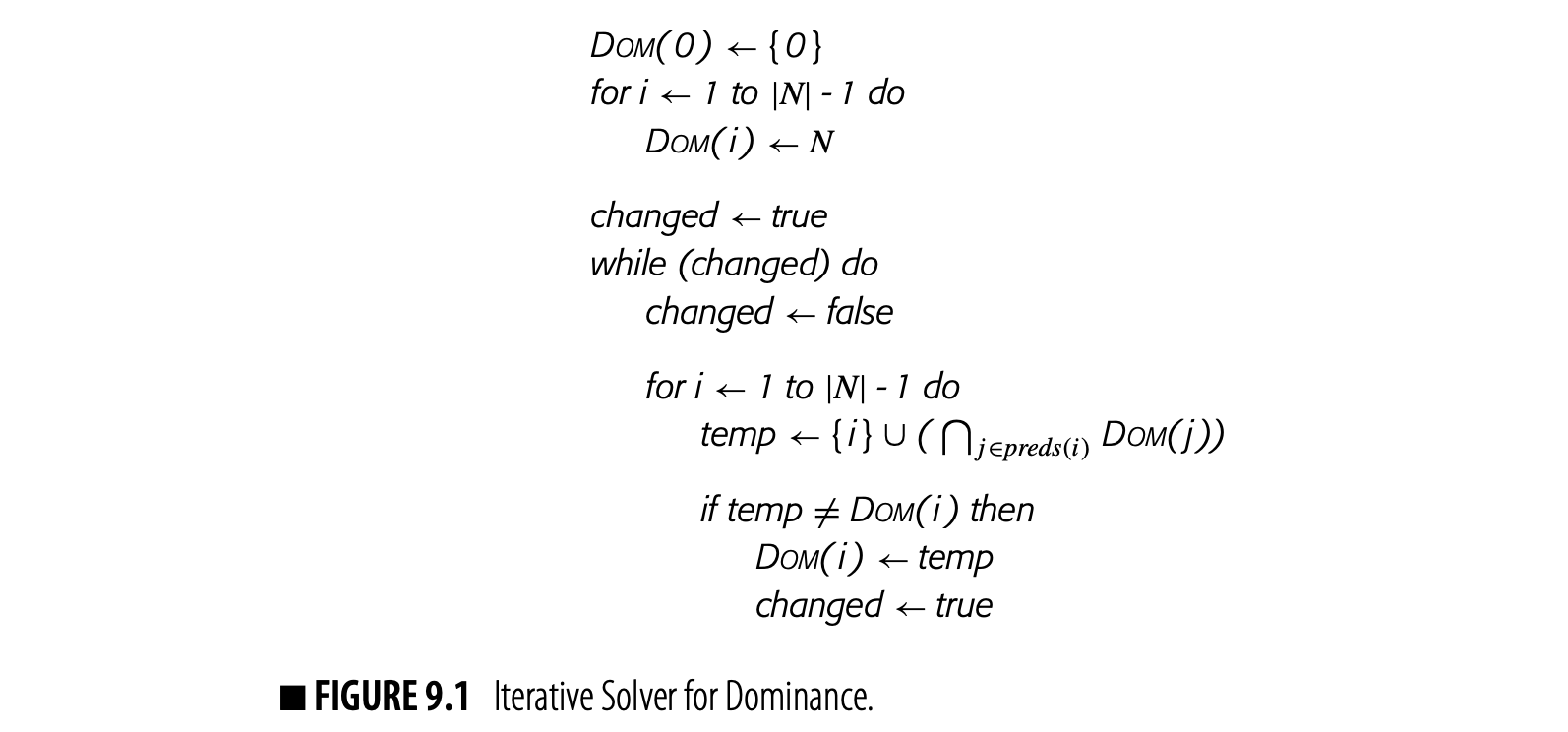

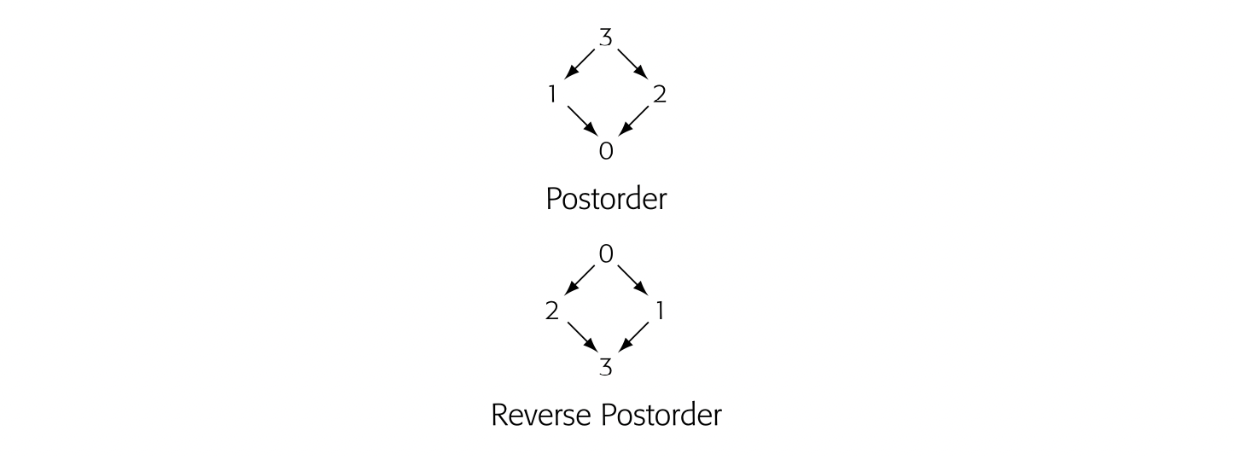

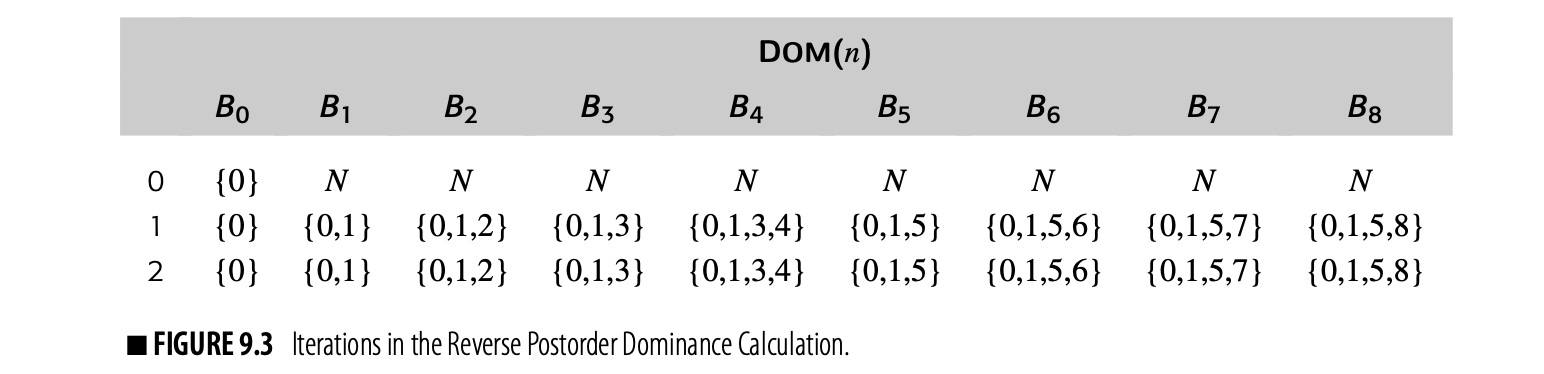

Fig. 9 shows a round-robin iterative solver for the dominance equations. It considers the nodes in order by their CFG name, , , , and so on. It initializes the Dom set for each node, then repeatedly recomputes those Dom sets until they stop changing.

Fig. 2 shows how the values in the Dom sets change as the computation proceeds. The first column shows the iteration number; iteration zero shows the initial values. Iteration one computes correct Dom sets for any node with a single path from , but computes overly large Dom sets for , , and . In iteration two, the smaller Dom set for corrects the set for , which, in turn shrinks Dom(). Similarly, the set for corrects the set for . Iteration three shows that the algorithm has reached a fixed point.

Three critical questions arise regarding this solution procedure. First, does the algorithm halt? It iterates until the Dom sets stop changing, so the argument for termination is not obvious. Second, does it produce correct Dom sets? The answer is critical if we are to use Dom sets in optimizations. Finally, how fast is the solver? Compiler writers should avoid algorithms that are unnecessarily slow.

Termination

Iterative calculation of the Dom sets halts because the sets that approximate Dom shrink monotonically throughout the computation. The algorithm initializes Dom to , and initializes the Dom sets for all other nodes to , the set of all nodes. A Dom set can be no smaller than and can be no larger than . Careful reasoning about the while loop shows that a Dom set, say Dom, cannot grow from iteration to iteration. Either it shrinks, as the Dom set of one of its predecessors shrinks, or it remains unchanged.

The while loop halts when it makes a pass over the nodes in which no Dom set changes. Since the Dom sets can only change by shrinking and those sets are bounded in size, the while loop must eventually halt. When it halts, it has found a fixed point for this particular instance of the Dom computation.

Correctness

Recall the definition of dominance. Node dominates if and only if every path from the entry node to contains . Dominance is a property of paths in the CFG.

Dom contains if and only if for all , or if . The algorithm computes Dom as plus the intersection of the Dom sets of all 's predecessors. How does this local computation over individual edges relate to the dominance property, which is defined over all paths through the CFG?

Meet operator In the theory of data-flow analysis, the meet is used to combine facts at a join point in the CFG. In the equations, the meet operator is set intersection.

The Dom sets computed by the iterative algorithm form a fixed-point solution to the equations for dominance. The theory of iterative data-flow analysis, which is beyond the scope of this text, assures us that a fixed point exists for these particular equations and that the fixed point is unique [221]. This "all-paths" formulation of Dom describes a fixed-point for the equations, called the meet-over-all-paths solution. Uniqueness guarantees that the fixed point found by the iterative algorithm is identical to the meet-over-all-paths solution.

Efficiency

Postorder number a labeling of the graph’s nodes that corre- sponds to the order in which a postorder traversal would visit them

Because the fixed-point solution to the Dom equations for a specific CFG is unique, the solution is independent of the order in which the solver computes those sets. Thus, the compiler writer is free to choose an order of evaluation that improves the analyzer's running time.

The compiler can compute RPO numbers in a postorder traversal if it starts a counter at and decrements the counter as it visits and labels each node.

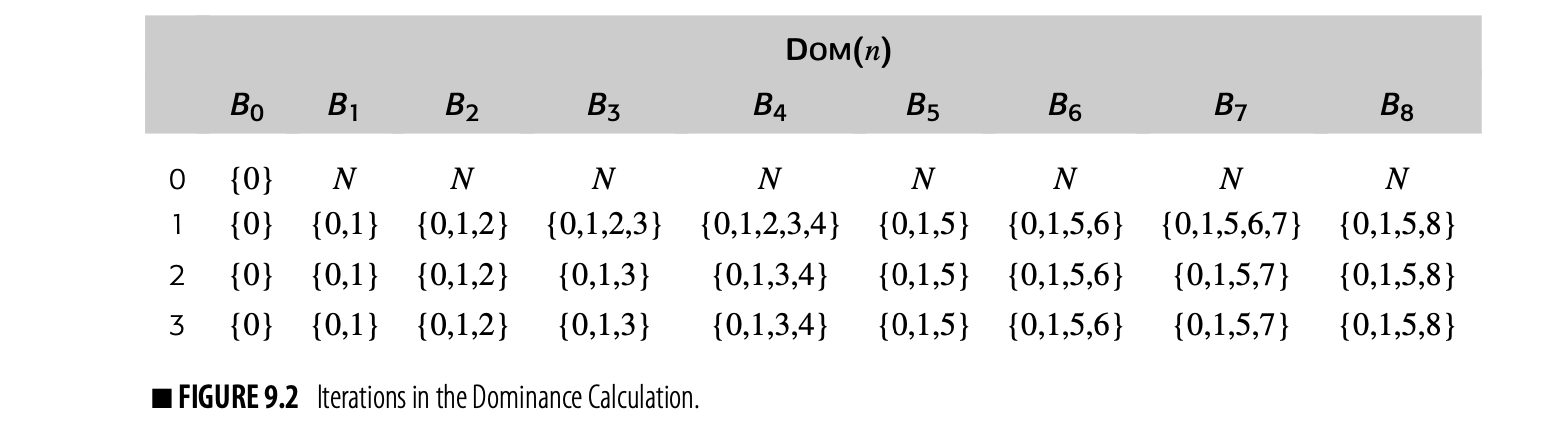

A (RPO) traversal of the graph is particularly effective for forward data-flow problems. If we assume that the postorder numbers run from zero to - 1, then a node's rpo number is simply - 1 minus that node's postorder number. Here, is the set of nodes in the graph.

An RPO traversal visits as many of a node's predecessors as possible, in a consistent order, before visiting the node. (In a cyclic graph, a node's predecessor may also be its descendant.) A postorder traversal has the opposite property; for a node , it visits as many of 's successors as possible before visiting . Most interesting graphs will have multiple rpo numberings; from the perspective of the iterative algorithm, they are equivalent.

For a forward data-flow problem, such as Dom, the iterative algorithm should use an rpo computed on the CFG. For a backward data-flow problem, such as LiveOut, the algorithm should use an rpo computed on the reverse cfg; that is, the cfg with its edges reversed. (The compiler may need to add a unique exit node to ensure that the reverse cfg has a unique entry node.)

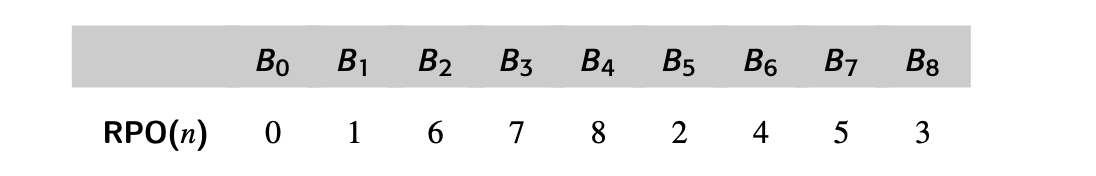

To see the impact of ordering, consider the impact of an rpo traversal on our example Dom computation. One rpo numbering for the example cfg, repeated in the margin, is:

Visiting the nodes in this order produces the sequence of iterations and val- ues shown in Fig. 9.3. Working in RPO, the algorithm computes accurate DOM sets for this graph on the first iteration and halts after the second iter- ation. RPO lets the algorithm halt in two passes over the graph rather than three. Note, however, that the algorithm does not always compute accurate DOM sets in the first pass, as the next example shows.

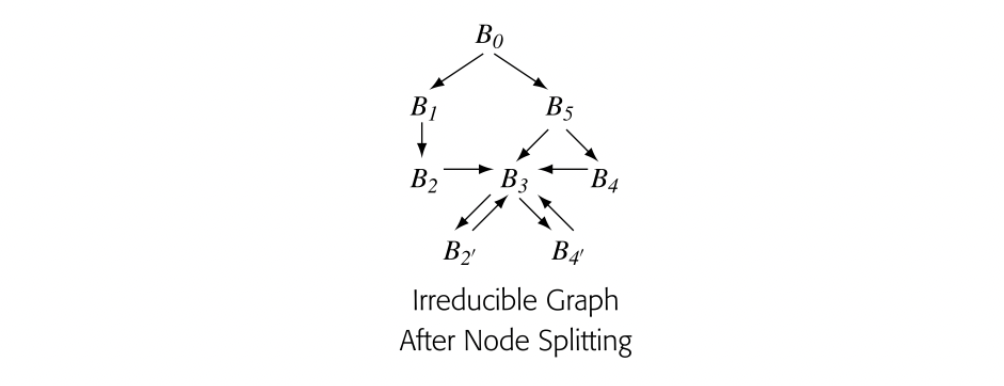

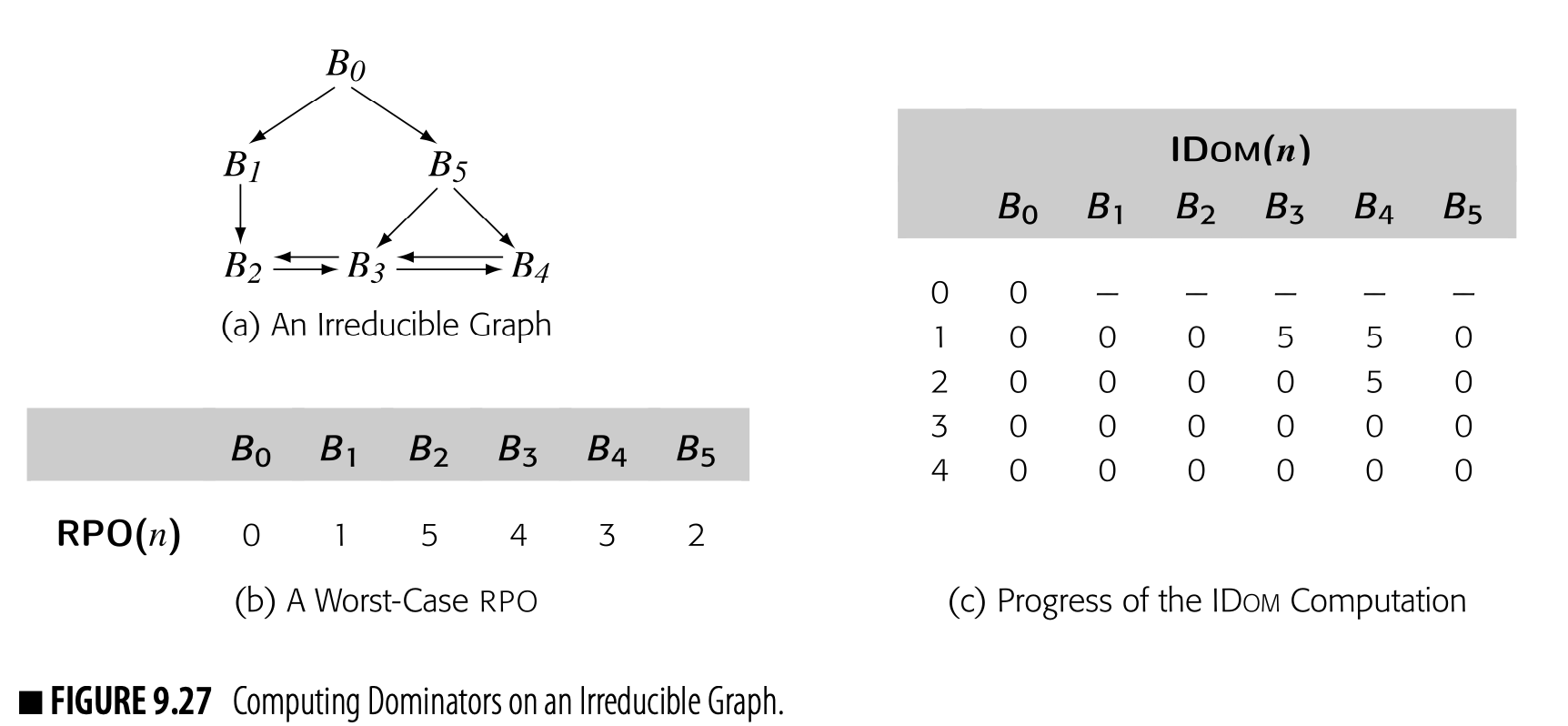

As a second example, consider the second CFG in the margin. It has two loops with multiple entries: and . In particular, has entries from both and , while has entries

from and . This property makes the graph irreducible, which makes it more difficult to analyze with some data-flow algorithms (see the discussion of reducibility in Section 9.5.1).

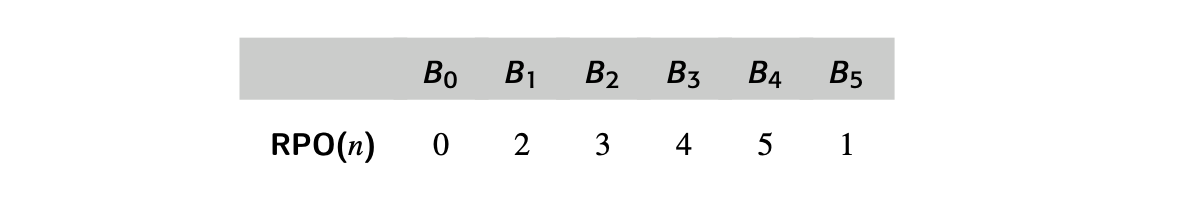

To apply the iterative algorithm, we need an rpo numbering. One rpo numbering for this CFG is:

Working in this order, the algorithm produces the following iterations:

Working in this order, the algorithm produces the following iterations:

The algorithm requires two iterations to compute the correct DOM sets. The final iteration recognizes that it has reached a fixed point.

The dominance calculation relies only on the structure of the graph. It ig- nores the behavior of the code in any of the CFG’s blocks. As such, it might be considered a form of control-flow analysis. Most data-flow problems in- volve reasoning about the behavior of the code and the flow of data between operations. As an example of this kind of calculation, we will revisit the analysis of live variables.

9.2.2 Live-VariableAnalysis

NAMING SETS IN DATA-FLOW EQUATIONS

In writing the data-flow equations for classic problems, we have renamed the sets that contain local information. The original papers use more intuitive set names. Unfortunately, those names clash with each other across problems. For example, available expressions, live variables, reaching definitions, and anticipable expressions all use some notion of a kill set. These four problems, however, are defined over three distinct domains: expressions (AVAILOUT and ANTOUT), definition points (REACHES), and variables (LIVEOUT). Thus, using one set name, such as KILL or KILLED, can produce confusion across problems.

The names that we have adopted encode both the domain and a hint as to the set’s meaning. Thus, VARKILL(n) contains the set of variables killed in block n, while EXPRKILL(n) contains the set of expressions killed in the same block. Similarly, UEVAR(n) is the set of upward-exposed variables in n, while UEEXPR(n) is the set of upward-exposed expressions. While these names are somewhat awkward, they make explicit the distinction between the notion of kill used in available expressions (EXPRKILL) and the one used in reaching definitions (DEFKILL).

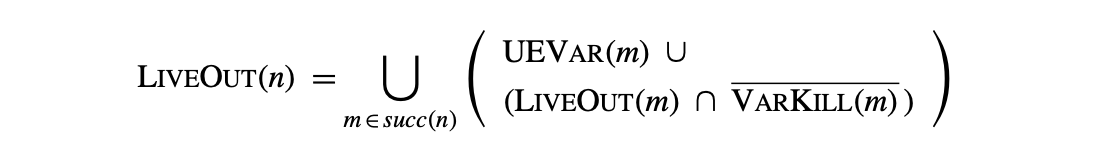

In Section 8.6.1, we used the results of live analysis to identify uninitialized variables. Compilers use live information for many other purposes, such as register allocation and construction of some variants of SSA form. We formulated live analysis as a global data-flow problem with the equation:

where, succ(n) refers to the set of CFG successors of . The analysis should initialize .

Comparing the equations for LiveOut and Dom reveals differences between the problems.

- LiveOut is a backward data-flow problem; is a function of the information known on entry to each of 's CFG successors. By contrast, Dom is a forward data-flow problem.

- LiveOut looks for a future use on any path in the CFG; thus, it combines information from multiple paths with the union operator. Dom looks for predecessors that lie on all paths from the entry node; thus, it combines information from multiple paths with the intersection operator.

- LiveOut reasons about the effects of operations. The sets and encode the effects of executing the block associated with . By contrast, the Dom equations only use node names. LiveOut uses more information and takes more space.

Despite the differences, the process for solving an instance of LiveOut is the same as for an instance of Dom. The compiler must: (1) build a CFG; (2) compute initial values for the sets (see Fig. 8.15(a) on page 420), and (3) apply the iterative algorithm (see Fig. 8.15(b)). These steps are analogous to those taken to solve the Dom equations.

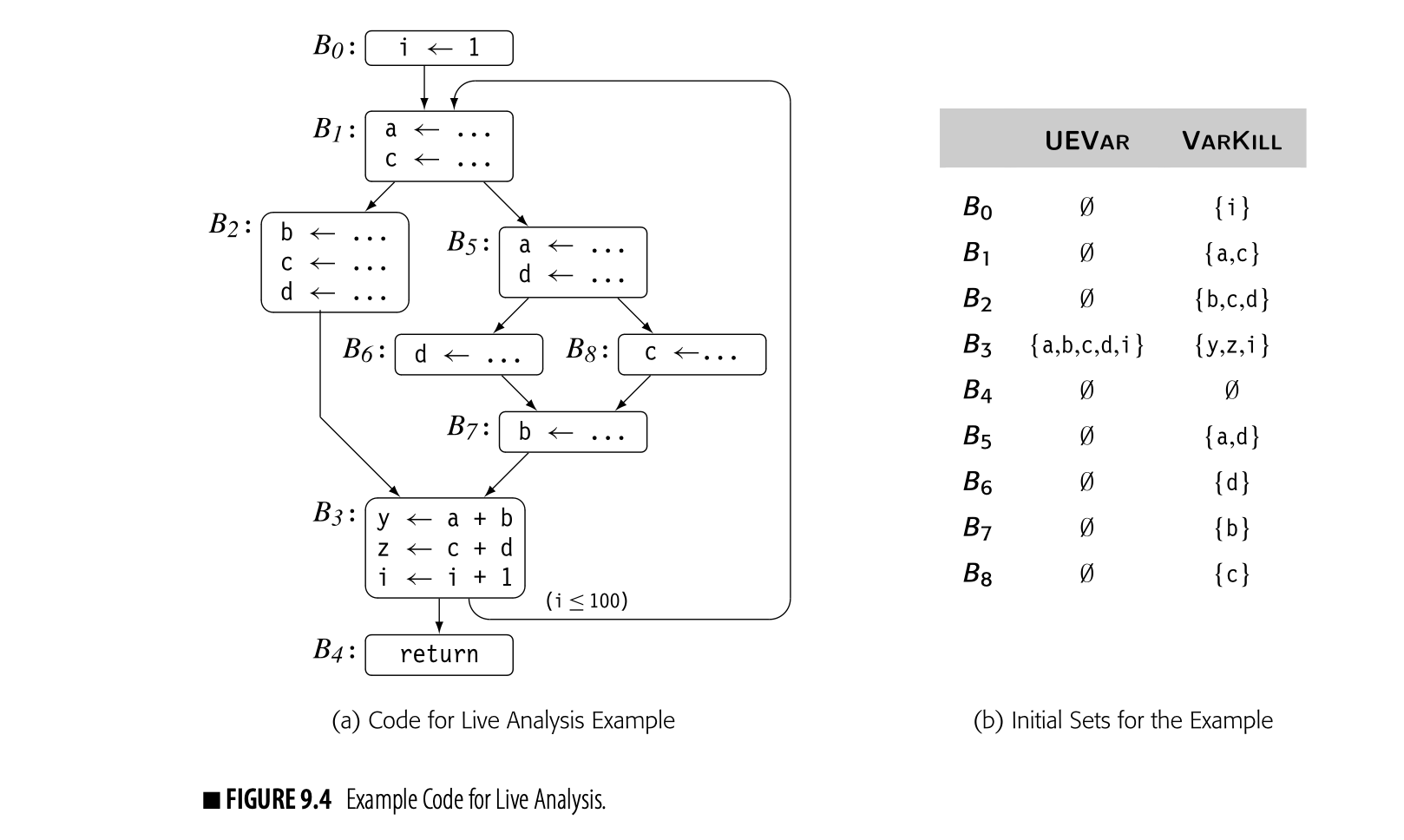

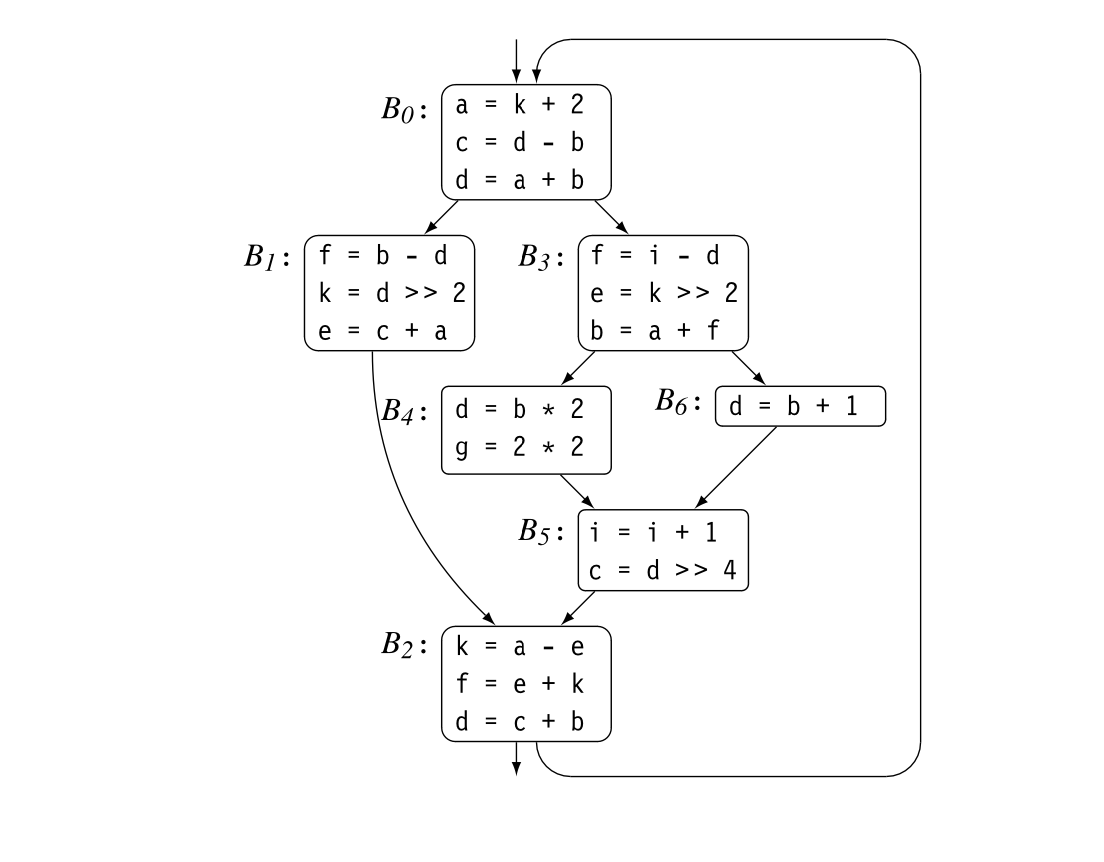

To see the issues that arise in solving an instance of LiveOut, consider the code shown in Fig. 9.4(a). It fleshes out the example CFG that we have used throughout this chapter. Panel (b) shows the UEVar and VarKill sets for each block.

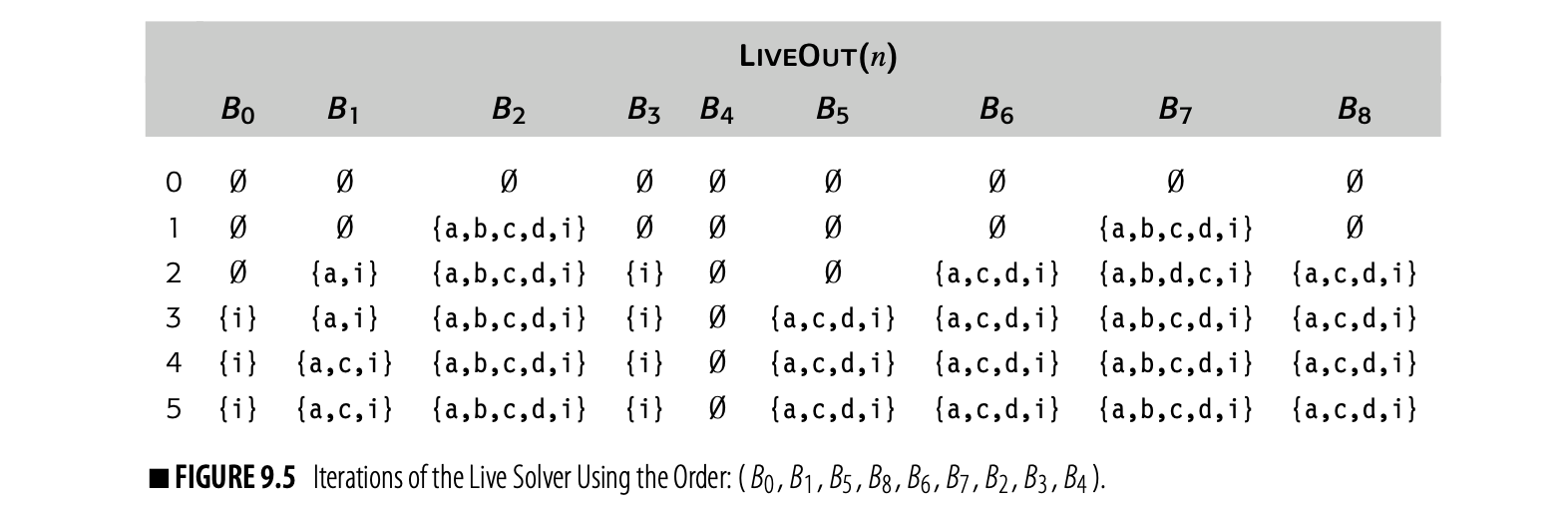

Fig. 9.5 shows the progress of the iterative solver on the example from Fig. 9.4(a), using the same RPO that we used in the Dom computation. Although the equations for LiveOut are more complex than those for Dom, the arguments for termination, correctness, and efficiency are similar to those for the dominance equations.

Termination

Recall that in DOM the sets shrink monoton- ically.

Iterative live analysis halts because the sets grow monotonically and the sets have a finite maximum size. Each time that the algorithm evaluates the LiveOut equation at a node in the cfg, that LiveOut set either remains the same or it grows larger. The LiveOut sets do not shrink. When the algorithm reaches a state where no LiveOut set changes, it halts. It has reached a fixed point.

The LiveOut sets are finite. Each LiveOut set is either , the set of names being analyzed, or it is a proper subset of . In the worst case, one LiveOut set would grow by a single name in each iteration; that behavior would halt after iterations, where is the number of nodes in the cfg.

The LiveOut sets are finite. Each LiveOut set is either , the set of names being analyzed, or it is a proper subset of . In the worst case, one LiveOut set would grow by a single name in each iteration; that behavior would halt after iterations, where is the number of nodes in the cfg.

This property-the combination of monotonicity and finite sets-guarantees termination. It is often called the finite descending chain property. In Dom, the sets shrink monotonically and their size is less than or equal to the number of nodes in the cfg. In LiveOut, the sets grow monotonically and their size is bounded by the number of names being analyzed. Either way, it guarantees termination.

Correctness

Iterative live analysis is correct if and only if it finds all the variables that satisfy the definition of liveness at the end of each block. Recall the definition: A variable is live at point if and only if there is a path from to a use of along which is not redefined. Thus, liveness is defined in terms of paths in the cfg. A path that contains no definitions of must exist from to a use of . We call such a path a -clear path.

should contain if and only if is live at the end of block . To form , the iterative solver computes the contribution to of each successor of in the cfg. The contribution of some successor to is given by the right-hand side of the equation: ().

The solver combines the contributions of the various successors with union because if is live on any path that leaves .

How does this local computation over single edges relate to liveness defined over all paths? The LiveOut sets that the solver computes are a fixed-point solution to the live equations. Again, the theory of iterative data-flow analysis assures us that the live equations have a unique fixed-point solution [221]. Uniqueness guarantees that all the fixed-point solutions are identical, which includes the meet-over-all-paths solution implied by the definition.

Efficiency

It is tempting to think that reverse postorder on the reverse CFG is equivalent to reverse preorder on the CFG. Exercise 3.b shows a counter-example.

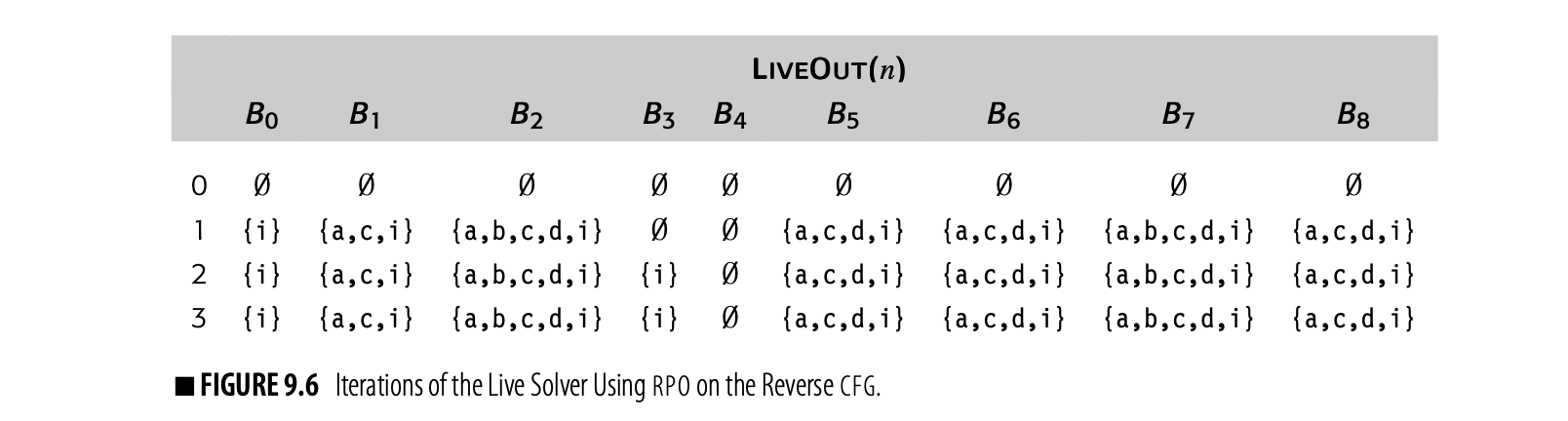

For a backward problem, the solver should use an rpo traversal on the reverse cfg. The iterative evaluation shown in Fig. 9.5 used rpo on the cfg. For the example cfg, one rpo on the reverse cfg is:

Visiting the nodes in this order produces the iterations shown in Fig. 9.6. Now, the algorithm halts in three iterations, rather than the five iterations required with a traversal ordered by rpo on the cfg. Comparing this table against the earlier computation, we can see why. On the first iteration, the algorithm computed correct LiveOut sets for all nodes except . It took a second iteration for because of the back edge--the edge from to . The third iteration is needed to recognize that the algorithm has reached its fixed point. Since the fixed point is unique, the compiler can use this more efficient order.

This pattern holds across many data-flow problems. The first iteration computes sets that are correct, except for the effects of cycles. Subsequent iterations settle out the information from cycles.

9.2.3 Limitations on Data-Flow Analysis

There are limits to what a compiler can learn from data-flow analysis. In some cases, the limits arise from the assumptions underlying the analysis. In other cases, the limits arise from features of the language being analyzed. To make informed decisions, the compiler writer must understand what data-flow analysis can do and what it cannot do.

When it computes , the iterative algorithm uses the sets , , and for each of 's CFG successors. This action implicitly assumes that execution can reach each of those successors; in practice, one or more of them may not be reachable.

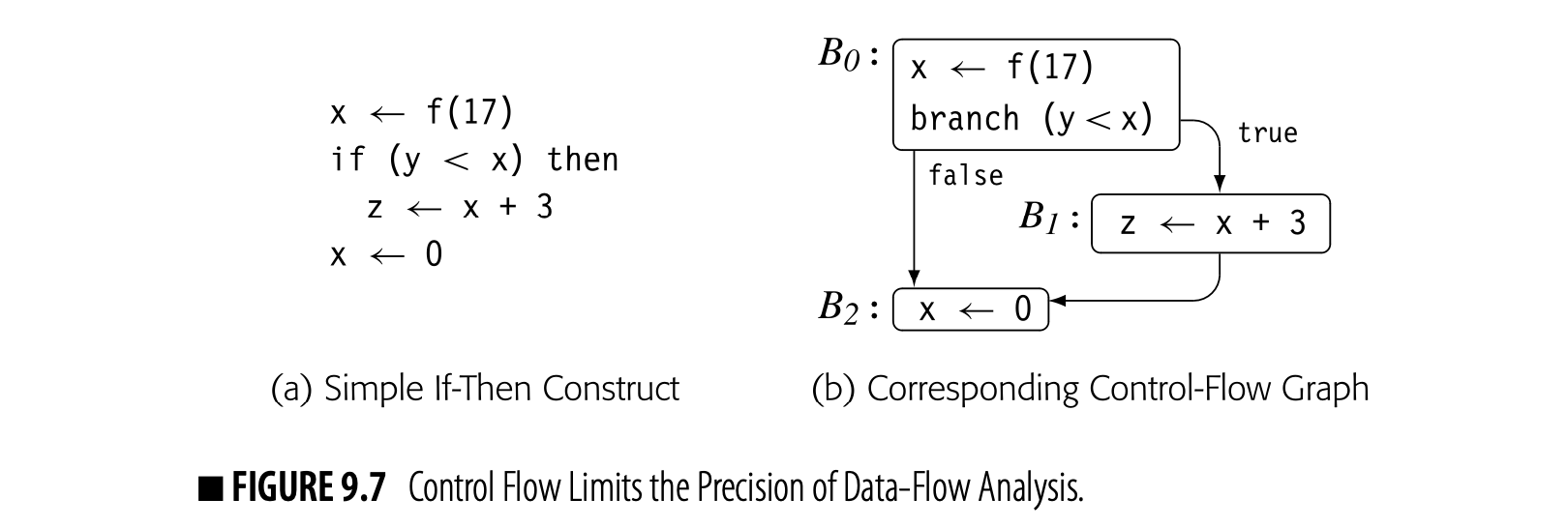

Consider the code fragment shown in Fig. 9.7 along with its CFG. The definition of x in is live on exit from because of the use of x in . The definition of x in kills the value set in . If cannot execute, then x's value from is not live past the comparison with y, and x # . If the compiler can prove that the y is always less than x, then never executes. The compiler can eliminate and replace the test and branch in with a jump to . At that point, if the call to f has no side effects, the compiler can also eliminate .

The equations for , however, take the union over all successors of a block, not just its executable successors. Thus, the analyzer computes:

Data-flow analysis assumes that all paths through the CFG are feasible. Thus, the information that they compute summarizes the possible data-flow events, assuming that each path can be taken. This limits the precision of the resulting information; we say that the information is precise "up to symbolic execution." With this assumption, x and both and must be preserved.

STATIC ANALYSIS VERSUS DYNAMIC ANALYSIS

The notion of static analysis leads directly to the question: What about dynamic analysis? By definition, static analysis tries to estimate, at compile time, what will happen at runtime. In many situations, the compiler cannot tell what will happen, even though the answer might be obvious with knowledge of one or more runtime values.

Consider, for example, the C fragment:

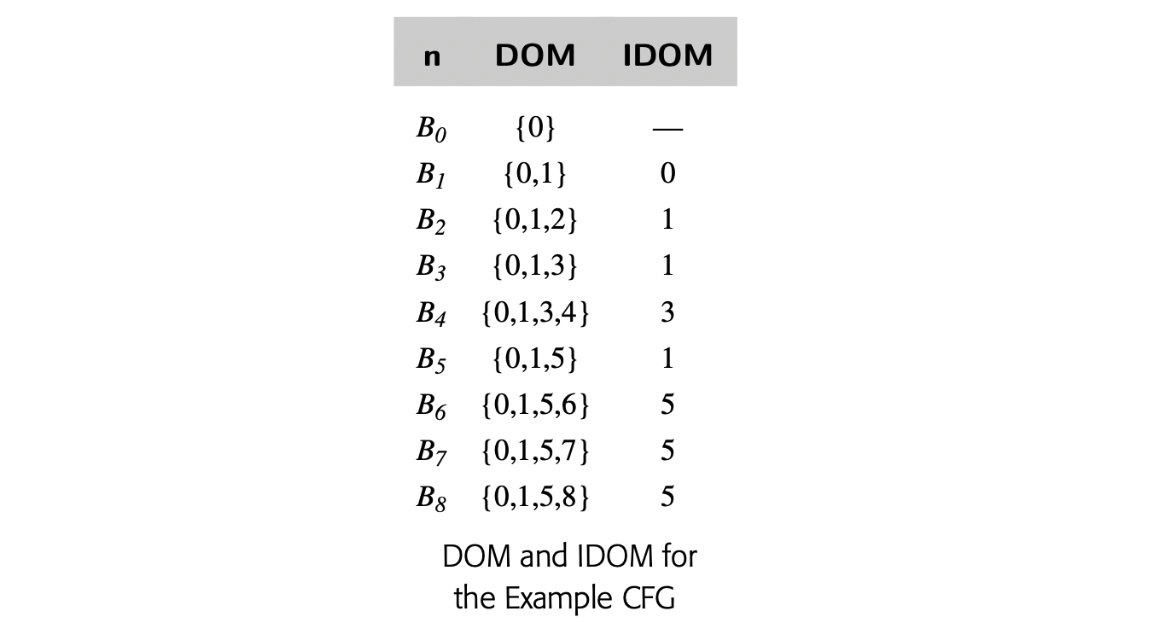

It contains a redundant expression, , if and only if p does not contain the address of either y or z. At compile time, the value of p and the address of y and z may be unknown. At runtime, they are known and can be tested. Testing these values at runtime would allow the code to avoid recomputing , where compile-time analysis might be unable to answer the question.

However, the cost of testing whether , or , or neither and acting on the result is likely to exceed the cost of recomputing y * z. For dynamic analysis to make sense, it must be a priori profitable—that is, the savings must exceed the cost of the analysis. This happens in some cases; in most cases, it does not. By contrast, the cost of static analysis can be amortized over multiple executions of the code, so it is more attractive, in general.

Another way that imprecision creeps into the results of data-flow analysis comes from the treatment of arrays, pointers, and procedure calls. An array reference, such as A[i,j], refers to a single element of A. However, without analysis that reveals the values of i and j, the compiler cannot tell which element of A is accessed. For this reason, compilers have traditionally treated a reference to an element of A as a reference to all of A. Thus, a use of A[i,j] counts as a use of A, and a definition of A[m,n] counts as a definition of A.

The compiler writer must not, however, make too strong an inference. Because the information on arrays is imprecise, the compiler must interpret that information conservatively. Thus, if the goal of the analysis is to determine where a value is no longer live--that is, the value must have been killed--then a definition of A[i,j] does not kill the value of A. If the goal is to recognize where a value might not survive, then a definition of A[i,j] might define any element of A.

Points-to analysis, used to track possible pointer values, is more expensive than classic data-flow problems such as DOM and LIVE.

Pointers add another level of imprecision to the results of static analysis. Explicit arithmetic on pointers makes matters worse. Unless the compiler employs an analysis that tracks the values of pointers, it must interpret an assignment to a pointer-based variable as a potential definition for every variable that the pointer might reach. Type safety can limit the set of objects that the pointer can define; a pointer declared to point at an object of type can only be used to modify objects of type . Without analysis of pointer values or a guarantee of type safety, assignment to a pointer-based variable can force the analyzer to assume that every variable has been modified. In practice, this effect often prevents the compiler from keeping the value of a pointer-based variable in a register across any pointer-based assignment. Unless the compiler can specifically prove that the pointer used in the assignment cannot refer to the memory location corresponding to the enregistered value, it cannot safely keep the value in a register.

The complexity of analyzing pointer use leads many compilers to avoid keeping values in registers if they can be the target of a pointer. Usually, some variables can be exempted from this treatment--such as a local variable whose address has never been explicitly taken. The alternative is to perform data-flow analysis aimed at disambiguating pointer-based references--reducing the set of possible variables that a pointer might reference at each point in the code. If the program can pass pointers as parameters or use them as global variables, pointer disambiguation becomes inherently interprocedural.

Procedure calls provide a final source of imprecision. To understand the data flow in the current procedure, the compiler must know what the callee can do to each variable that is accessible to both the caller and the callee. The callee may, in turn, call other procedures that have their own potential side effects.

Unless the compiler computes accurate summary information for each procedure call, it must estimate the call's worst-case behavior. While the specific assumptions vary across problems and languages, the general rule is to assume that the callee both uses and modifies every variable that it can reach. Since few procedures modify and use every variable, this rule typically overestimates the impact of a call, which introduces further imprecision into the results of the analysis.

9.2.4 Other Data-Flow Problems

Compilers use data-flow analyses to prove the safety of applying transformations in specific situations. Thus, many distinct data-flow problems have been proposed, each for a particular optimization.

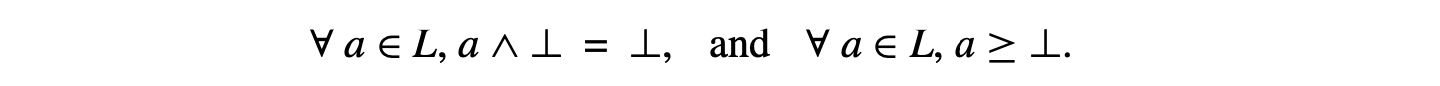

Availability

Availability An expression is available at point if and only if, on every path from the procedure's entry to , is evaluated and none of its operands is redefined.

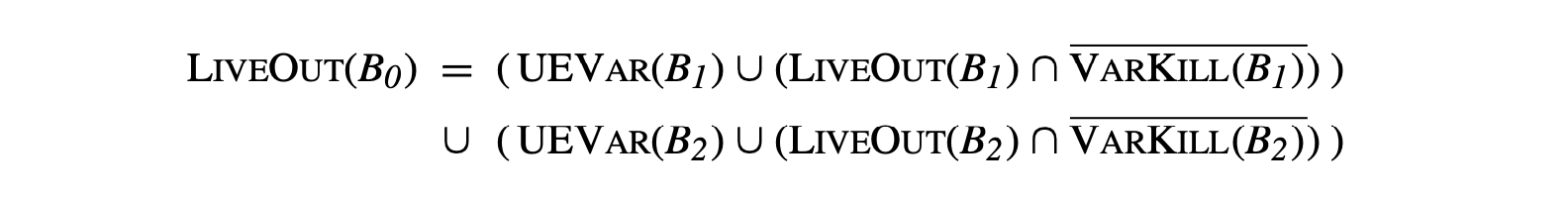

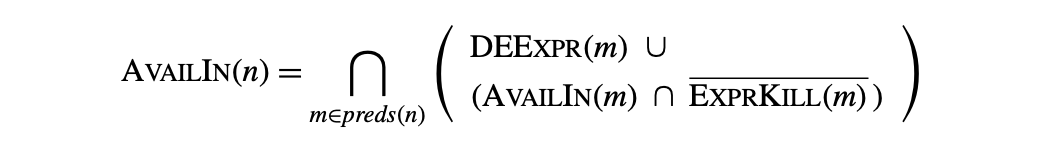

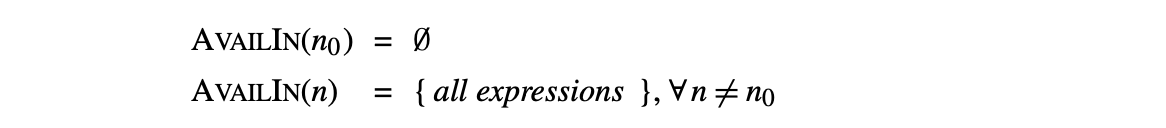

To identify redundant expressions, the compiler can compute information about the availability of expressions. This analysis annotates each node in the CFG with a set , which contains the names of all expressions in the procedure that are available on entry to the block corresponding to . The equations for are:

with initial values for the sets:

with initial values for the sets:

These equations can be solved efficiently with a standard iterative data-flow solver. Since it is a forward data-flow problem, the solver should use RPO on the CFG.

These equations can be solved efficiently with a standard iterative data-flow solver. Since it is a forward data-flow problem, the solver should use RPO on the CFG.

In the equations, is the set of downward-exposed expressions in . An expression if and only if block evaluates and none of 's operands is defined between the last evaluation of in and the end of . contains all those expressions that are killed by a definition in . An expression is killed if one or more of its operands are redefined in the block.

An expression is available on entry to if and only if it is available on exit from each of 's predecessors in the CFG. As the equation states, an expression is available on exit from some block if one of two conditions holds: either is downward exposed in , or it is available on entry to and is not killed in .

AvailIn sets are used in global redundancy elimination, sometimes called global common subexpression elimination. Perhaps the simplest way to achieve this effect is to compute sets for each block and use them as initial information in local value numbering (see Section 46.1). Lazy code motion is a stronger form of redundancy elimination that also uses availability (see Section 46.1).

Reaching Definitions

In some cases, the compiler needs to know where an operand was defined. If multiple paths in the CFG lead to the operation, then multiple definitions may provide the value of the operand. To find the set of definitions that reacha block, the compiler can compute reaching definitions. The compiler annotates each node in the CFG with a set, that contains the name of every definition that reaches the head of the block corresponding to . The domain of is the set of definition points in the procedure--the set of assignments.

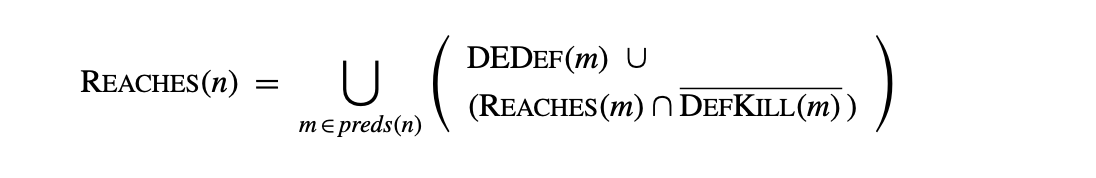

The compiler computes a set for each CFG node using the equation:

with initial values for the Reaches sets:

with initial values for the Reaches sets:

is the set of downward-exposed definitions in : those definitions in for which the defined name is not subsequently redefined in . contains all the definition points that are obscured by a definition of the same name in ; if defines some name and contains a definition that also defines . Thus, contains those definition points that survive through .

is the set of downward-exposed definitions in : those definitions in for which the defined name is not subsequently redefined in . contains all the definition points that are obscured by a definition of the same name in ; if defines some name and contains a definition that also defines . Thus, contains those definition points that survive through .

and are both defined over the set of definition points, but computing each of them requires a mapping from names (variables and compiler-generated temporaries) to definition points. Thus, gathering the initial information for reaching definitions is more expensive than it is for live variables.

Anticipable Expressions

Anticipability An expression, , is anticipable at point if and only if (1) every path that leaves evaluates , and (2) evaluating at would produce the same result as the first evaluation along each of those paths.

In some situations, the compiler can move an expression backward in the CFG and replace multiple instances of the , along different paths, with a single instance. This optimization, called hoisting, reduces code size. It does not change the number of times the expression is evaluated.

To find safe opportunities for hoisting, the compiler can compute the set of anticipable expressions at the end of each block. An expression is anticipable at the end of block if the next evaluation of , along each path leaving , would produce the same result. The equations require that be computed along every path that leaves .

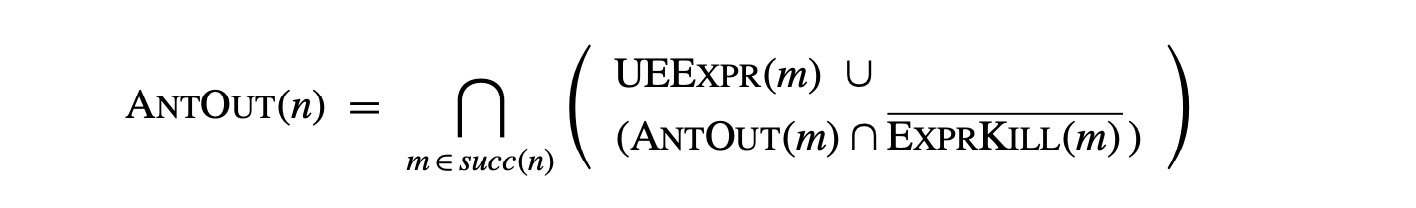

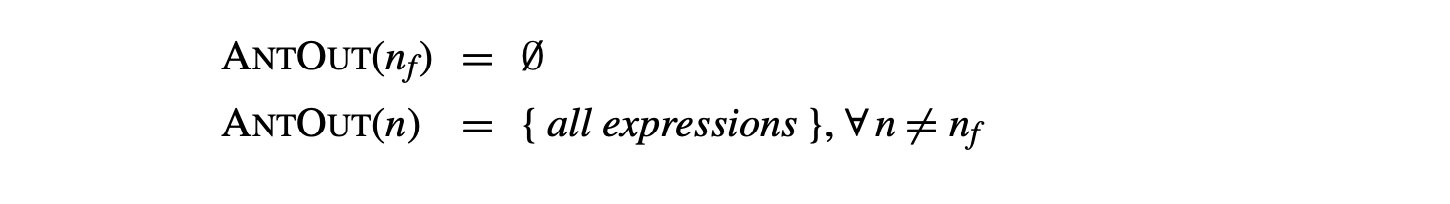

, the set of expressions anticipable at the end of a block, can be computed as a backward data-flow problem on the CFG. Anticipability is formulated over the domain of expressions.

Implementing Data-Flow Frameworks

The equations for many global data-flow problems show a striking similarity. For example, available expressions, live variables, reaching definitions, and anticipable expressions all have propagation functions of the form:

where and are constants derived from the code and and are standard set operations such as and . This similarity appears in the problem descriptions; it creates the opportunity for code sharing in the implementation of the analyzer.

The compiler writer can easily abstract away the details in which these problems differ and implement a single, parameterized analyzer. The analyzer needs functions to compute and , implementations of the operators, and an indication of the problem's direction. In return, it produces the desired data-flow sets.

This implementation strategy encourages code reuse. It hides the low-level details of the solver. It also creates a situation in which the compiler writer can profitably invest effort in optimizing the implementation. For example, a scheme that implements as a single function may outperform one that implements both and , and computes as . A framework lets all the client transformations benefit from improvements in the set representations and operator implementations.

The equations to define AntOut are:

with initial values for the AntOut sets:

Here is the set of upward-exposed expressions—those used in before they are killed. contains all those expressions that are killed by a definition in ; it also appears in the equations for available expressions.

Here is the set of upward-exposed expressions—those used in before they are killed. contains all those expressions that are killed by a definition in ; it also appears in the equations for available expressions.

The results of anticipability analysis are used in lazy code motion, to de- crease execution time, and in code hoisting, to shrink the size of the compiled code. Both transformations are discussed in Section 10.3.

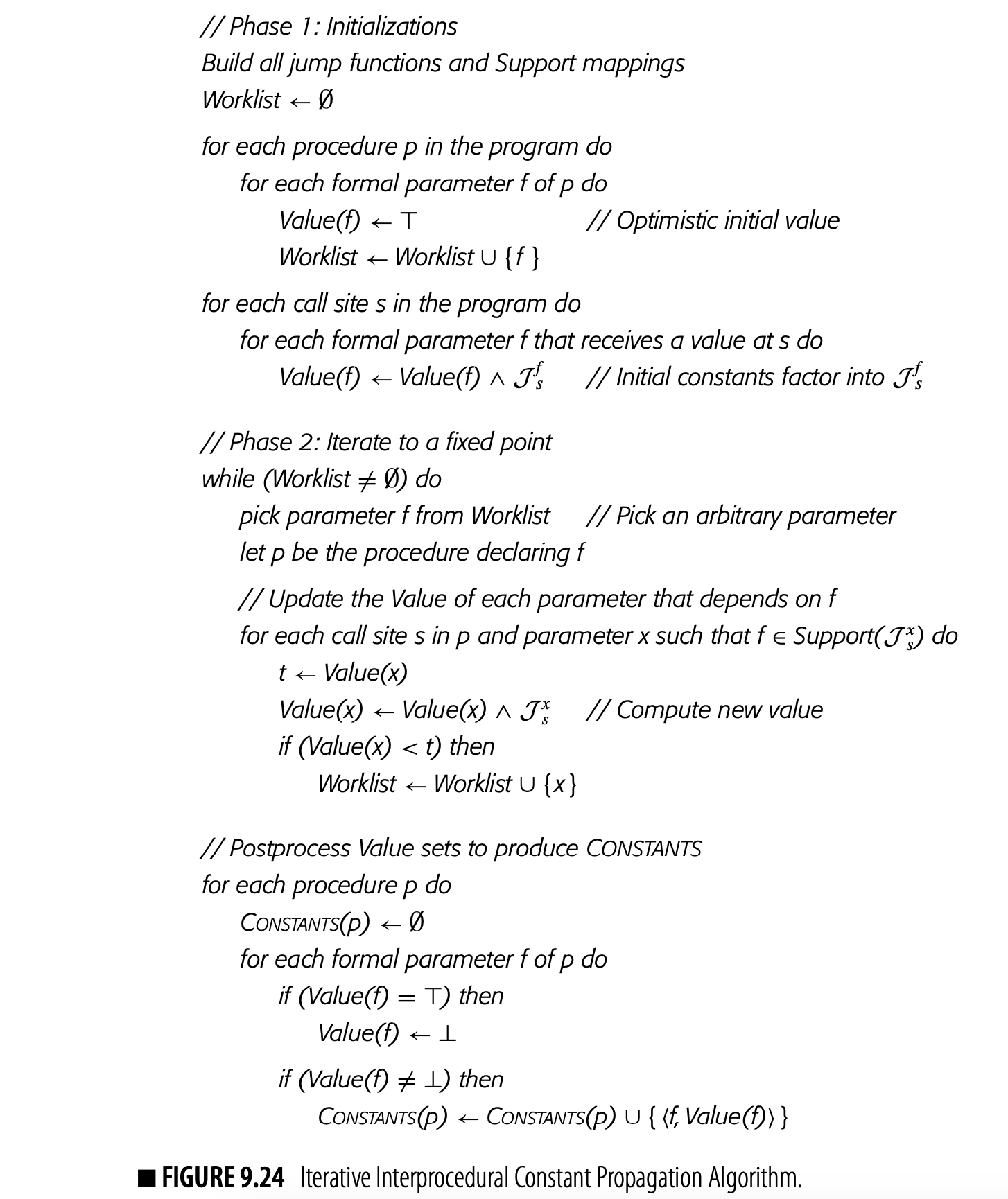

Interprocedural Summary Problems

When analyzing a single procedure, the compiler must account for the impact of each procedure call. In the absence of specific information about the call, the compiler must make worst-case assumptions about the callee and about any procedures that it, in turn, calls. These assumptions can seriously degrade the precision of the global data-flow information. For example, the compiler must assume that the callee modifies every variable that it can access; this assumption essentially stops the propagation of facts across a call site for all global variables, module-level variables, and call-by-reference parameters.

To limit such impact, the compiler can compute summary information on each call site. The classic summary problems compute the set of variables that might be modified as a result of the call and that might be used as a result of the call. The compiler can then use these computed summary sets in place of its worst case assumptions.

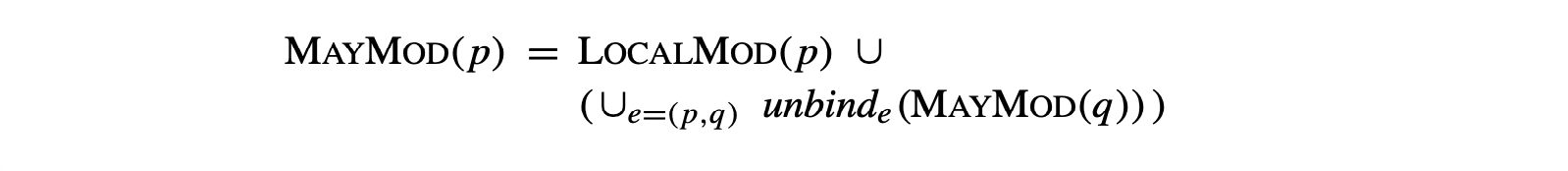

Flow insensitive This formulation of MAYMOD ignores control flow inside procedures. Such a formulation is said to be flow .

The may modify problem_ annotates each call site with a set of names that the callee, and procedures it calls, might modify. May modify is one of the simplest problems in interprocedural analysis, but it can have a significant impact on the quality of information produced by other analyses, such as global constant propagation. May modify is posed as a set of data-flow equations over the program's call graph that annotate each procedure with a MayMod set.

is initialized to contain all the names modified locally in that are visible outside . It is computed as the set of names defined in minus any names that are strictly local to .

The function maps one set of names into another. For a call-graph edge and set of names , maps each name in s from the name space of to the name space that holds at the call site, using the bindings at the call site that corresponds to . In essence, it projects s from 's name space into p 's name space.

Given a set of sets and a call graph, an iterative solver will find a fixed-point solution for these equations. It will not achieve the kind of fast time bound seen in global data-flow analysis. A more complex framework is required to achieve near-linear complexity on this problem (see Chapter Notes).

The MayMod sets computed by these equations are generalized summary sets. That is, MayMod() contains the names of variables that might be modified by a call to , expressed in the name space of . To use this information at a specific call site that invokes , the compiler will compute the set , where is the call graph edge corresponding to the call. The compiler must then add to any names that are aliased inside to names contained in .

The compiler can also compute the set of variables that might be referenced as a result of executing a procedure call, the interprocedural may reference problem. The equations to annotate each procedure with a set MayRef() are similar to the equations for The function unbind e_{e} maps one set of names into another. For a call-graph edge e=(p, q) and set of names s, unbind d_{e}(s) maps each name in s from the name space of q to the name space that holds at the call site, using the bindings at the call site that corresponds to e. In essence, it projects s from q 's name space into p 's name space.\\Given a set of LOCALMOD sets and a call graph, an iterative solver will find a fixed-point solution for these equations. It will not achieve the kind of fast time bound seen in global data-flow analysis. A more complex framework is required to achieve near-linear complexity on this problem (see Chapter Notes)..

Section Review

Iterative data-flow analysis works by repeatedly reevaluating an equation at each node in some underlying graph until the sets defined by the equations reach a fixed point. Many data-flow problems have a unique fixed point, which ensures a correct solution independent of the evaluation order, and the finite descending chain property, which guarantees termination independent of the evaluation order. These two properties allow the compiler writer to choose evaluation orders that converge quickly. As a result, iterative analysis is robust and efficient.

The literature describes many different data-flow problems. Examples in this section include dominance, live analysis, availability, anticipability, and interprocedural summary problems. All of these, save for the interprocedural problems, have straightforward efficient solutions with the iterative algorithm. To avoid solving multiple problems, compilers often turn to a unifying framework, such as SSA form, described in the next section.

Review Questions

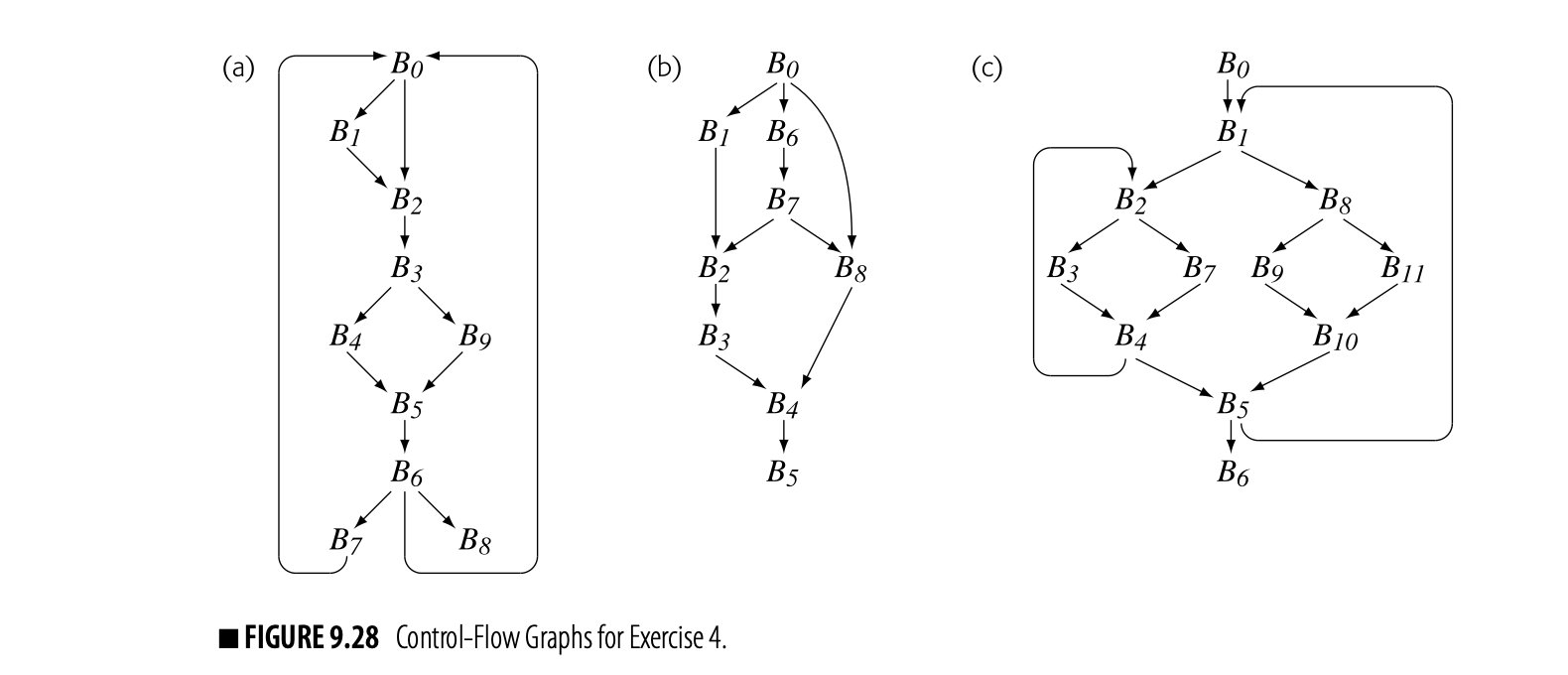

- Compute Dom sets for the CFG shown in the margin, evaluating the nodes in the order . Explain why this order takes a different number of iterations than is shown on page 456.

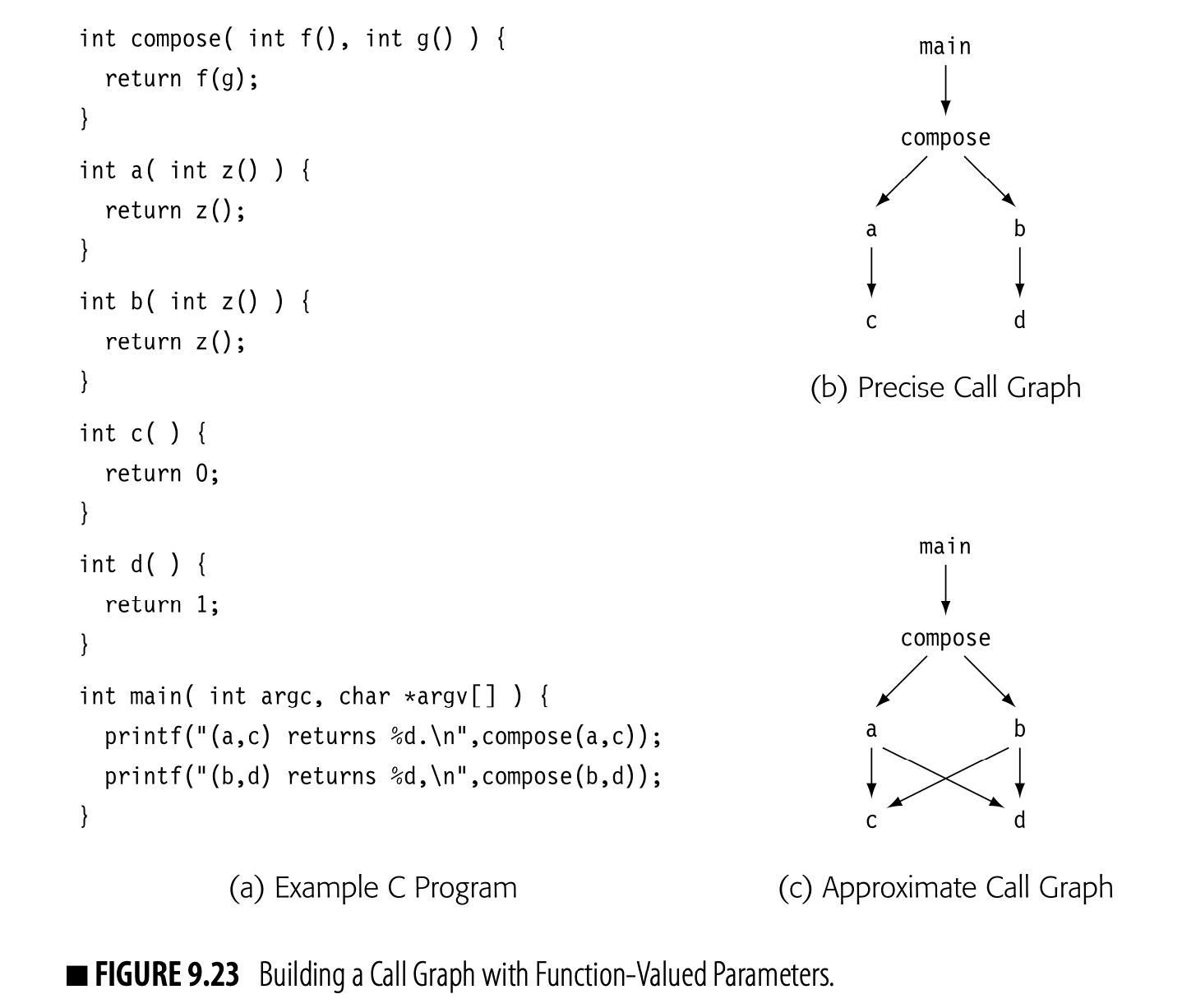

- When the compiler builds a call graph, ambiguous calls can complicate the process, much as ambiguous jumps complicate CFG construction. What language features might lead to an ambiguous call site--one where the compiler was uncertain of the callee5 identify?

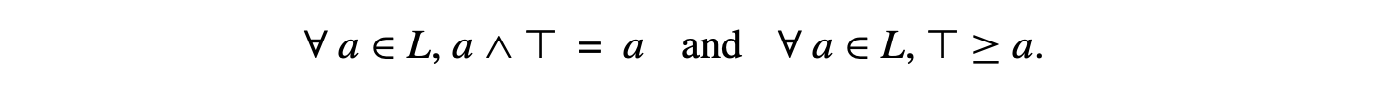

9.3 Static Single-Assignment Form

Over time, compiler writers have formulated many different data-flow problems. If each transformation uses its own analysis, the effort spent implementing, debugging, and maintaining the analysis passes can grow unreasonably large. To limit the number of analyses that the compiler writer must implement and that the compiler must run, it is desirable to use a single analysis for multiple transformations.

Some compilers, such as LLVM/CLANG, use SSA as their definitive IR.

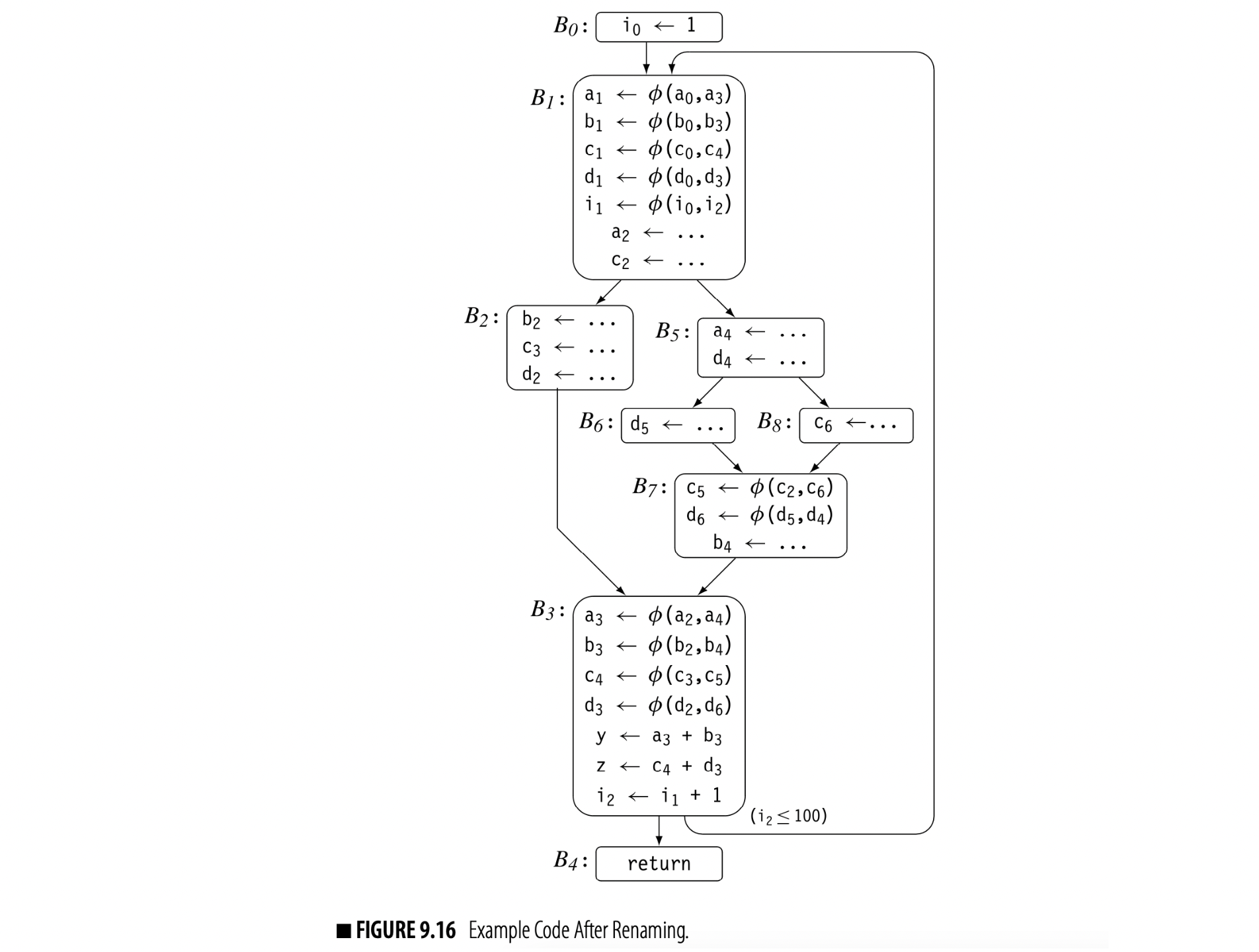

One strategy for such a "universal" analysis is to build an IR called static single-assignment form (ssa) (see also Section 4.6.2). SSA encodes both data flow and control flow directly into the IR. Many of the classic scalar optimizations have been reworked to operate on code in SSA form.

Code in SSA form obeys two rules:

- Each computation in the procedure defines a unique name.

- Each use in the procedure refers to a single name.

The first rule removes the effect of "kills" from the code; any expression in the code is available at any point after it has been evaluated. (We first saw this effect in local value numbering.) The second rule has a more subtle effect. It ensures that the compiler can still represent the code concisely and correctly; a use can be written with a single name rather than a long list of all the definitions that might reach it.

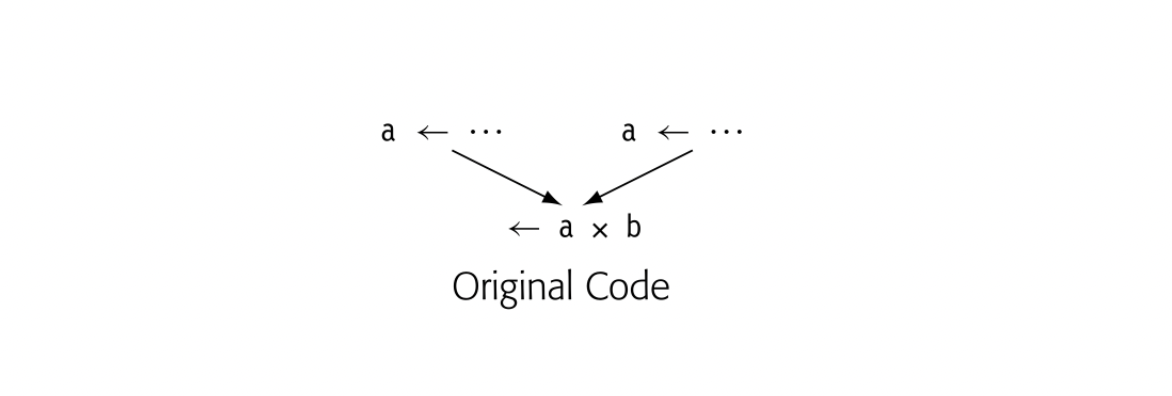

Consider the small example shown in the margin. If the compiler renames the two definitions of a to a and, what name should appear in the use of a in a? Neither nor will work in a?b. (The example assumes that was defined earlier in the code.)

Consider the small example shown in the margin. If the compiler renames the two definitions of a to a and, what name should appear in the use of a in a? Neither nor will work in a?b. (The example assumes that was defined earlier in the code.)

To manage this name space, the SSA construction inserts a special kind of copy operation, a -function, at the head of the block where control-flow paths meet, as shown in the margin. When the -function evaluates, it reads the argument that corresponds to the edge from which control flow entered the block. Thus, coming from the block on the left, the -function reads, while from the block on the right it reads. The selected argument is assigned to. Thus, the evaluation of computes the same value that did in the pre-SSA code.

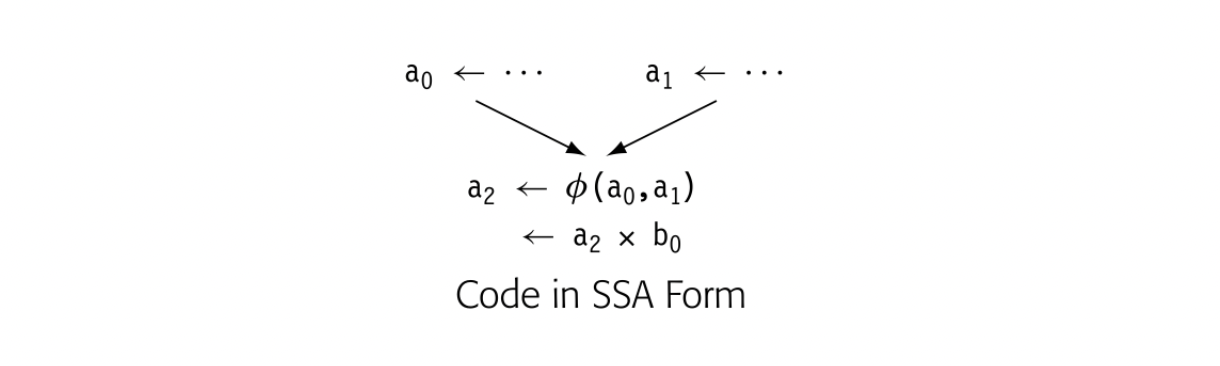

Fig. 9.8 shows a more extensive example. Consider the various uses of the variable in the code fragment shown in panel (a). The curved gray lines show which definitions can reach each use of . Panel (b) shows the same fragment in SSA form. Variables have been renamed with subscripts to ensure unique names for each definition. We assume that, and are defined earlier in the code.

Fig. 9.8 shows a more extensive example. Consider the various uses of the variable in the code fragment shown in panel (a). The curved gray lines show which definitions can reach each use of . Panel (b) shows the same fragment in SSA form. Variables have been renamed with subscripts to ensure unique names for each definition. We assume that, and are defined earlier in the code.

The code in panel (b) includes all of the -functions needed to reconcile the names generated by rule one with the need for unique names in uses. Tracing the flow of values will reveal that the same values follow the same paths as in the original code.

Two final points about -functions need explanation. First, -functions are defined to execute concurrently. When control enters a block, all of the block's -functions read their designated argument, in parallel. Next, they all define their target names, in parallel. This concurrent execution semantics allows the SSA construction algorithm to ignore the order of -functions as it inserts them into a block.

Second, by convention, we write the arguments of a -function left-to-right to correspond with the incoming edges left-to-right on the printed page. Inside the compiler, the IR has no natural notion of left-to-right for the edges entering a block. Thus, the implementation will require some bookkeeping to track the correspondence between -function arguments and CFG edges.

9.3.1 A Naive Method for Building SSA Form

Both of the SSA-construction algorithms that we present follow the same basic outline: (1) insert -functions as needed and (2) rename variables and temporary values to conform with the two rules that define SSA form. The simplest construction method implements the two steps as follows:

The "naive" algorithm inserts more -functions than are needed. It adds a - function for each name at each join point.

- Inserting -functions At the start of each block that has multiple CFG predecessors, insert a -function, such as x (x,x), for each name x that the current procedure defines. The -function should have one argument for each predecessor block in the CFG. This process inserts a -function in every case that might need one. It also inserts many extraneous -functions.

- Renaming The -function insertion algorithm ensures that a -function for is in place at each join point in the CFG reached by two or more definitions of . The renaming algorithm rewrites all of the names into the appropriate SSA names. The first step adds a unique subscript to the name at each definition.

Base name In an SSA name , the base name is x and the version is 2 .

At this point, each definition has a unique SSA name. The compiler can compute reaching definitions (see Section 9.2.4) to determine which SSA name reaches each use. The compiler writer must change the meaning of DefKill so that a definition to one SSA name kills not only that SSA name but also all SSA names with the same base name. The effect is to stop propagation of an SSA name at any -function where it is an argument. With this change, exactly one definition--one SSA name--reaches each use. The compiler makes a pass over the code to rewrite the name in each use with the SSA name that reaches it. This process rewrites all the uses, including those in -function arguments. If the same SSA name reaches a -function along multiple paths, the corresponding -function arguments will have the same SSA name. The compiler must sort out the correspondence between incoming edges in the CFG and -function arguments so that it can rename each argument with the correct SSA name. While conceptually simple, this task requires some bookkeeping.

A -function is redundant. A -function whose value is not live is considered dead.

The naive algorithm constructs SSA form that obeys the two rules. Each definition assigns to a unique name; each reference uses the name of a distinct definition. While the algorithm builds correct SSA form, it can insert -functions that are redundant or dead. These extra -functions may be problematic. The compiler wastes memory representing them and time traversing them. They can also decrease the precision of some kinds of analysis over SSA form.

We call this flavor of SSA maximal SSA form. To build SSA form with fewer -functions requires more work; in particular, the compiler must analyze the code to determine where potentially distinct values converge in the CFG. This computation relies on the dominance information described in Section 9.2.1.

The difference of SSA form of SSA Form

The literature proposes several distinct flavors of SSA form. The flavors differ in their criteria for inserting -functions. For a given program, they can produce different sets of -functions.

Minimal SSA inserts a -function at any join point where two distinct definitions for the same original name meet. This is the minimal number consistent with the definition of SSA. Some of those -functions, however, may be dead; the definition says nothing about the values being live when they meet.

Pruned SSA adds a liveness test to the -insertion algorithm to avoid adding dead -functions. The construction must compute LwEOUT sets, which increases the cost of building pruned SSA.

Semipruned SSA is a compromise between minimal SSA and pruned SSA. Before inserting -functions, the algorithm eliminates any names that are not live across a block boundary. This can shrink the name space and reduce the number of -functions without the overhead of computing LwEOUT sets. The algorithm in Fig. 9.11 computes semipruned SSA.

Of course, the number of -functions depends on the specific program being converted into SSA form. For some programs, the reductions obtained by semipruned SSA and pruned SSA are significant. Shrinking the SSA form can lead to faster compilation, since passes that use SSA form then operate on programs that contain fewer operations--and fewer -functions.

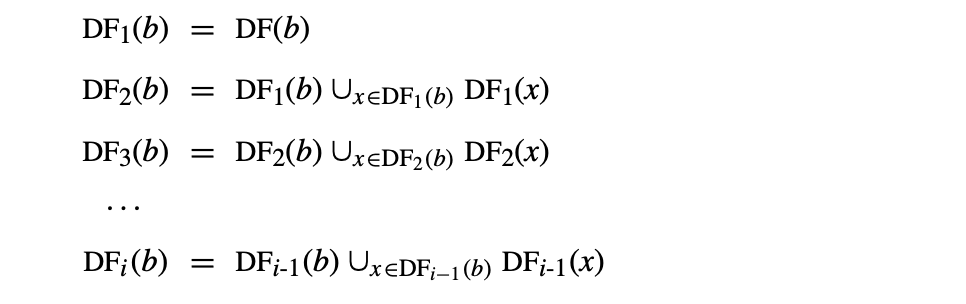

The following subsections present, in detail, an algorithm to build semipruned SSA--a version with fewer -functions. Section 9.3.2 introduces dominance frontiers and shows how to compute them; dominance frontiers guide -function insertion. Section 9.3.3 gives an algorithm to insert -functions, and Section 9.3.4 presents an efficient algorithm for renaming. Section 9.3.5 discusses complications that can arise in translating out of SSA form.

9.3.2 Dominance Frontiers

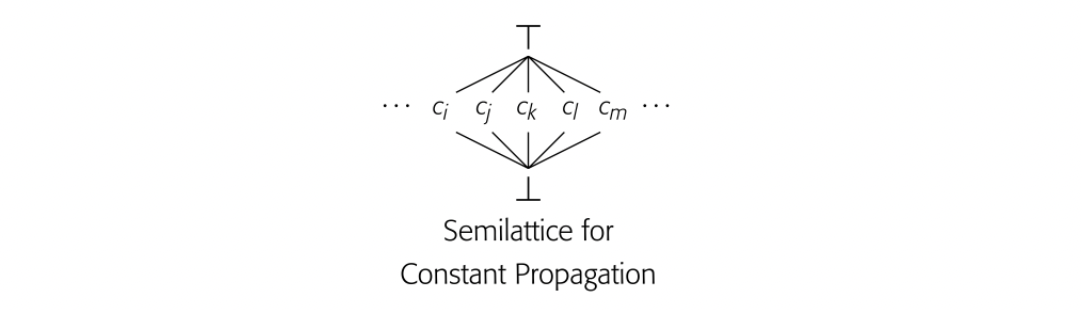

The primary problem with maximal SSA form is that it contains too many -functions. To reduce their number, the compiler must determine more carefully where they are needed. The key to -function insertion lies in understanding which names need a -function at each join point. To solve this problem efficiently and effectively, the compiler can turn the question around. It can determine, for each block , the set of blocks that will need a -function as the result of a definition in block . Dominance plays a critical role in this computation.

Consider the CFG shown in the margin. Assume that the code assigns distinct values to in both and , and that no other block assigns to . The value from is the only value for that can reach , , and . Because dominates these three blocks, it lies on any path from to , , or . The definition in cannot reach them.

Strict dominance In a CFG, node strictly dominates node if and . We denote this as .

presents a different situation. Neither of its CFG predecessors, and , dominate . A use of in can receive its value from either or , depending on the path taken to reach . The assignments to in and force a -function for at the start of .

dominates the region . It is the immediate dominator of all three nodes. A definition of in will reach a use in that region, unless is redefined before the use. The definition in cannot necessitate the need for a -function in this region.

Strict dominance In a CFG, node p strictly dominates node q if and . We denote this as .

lies just outside of the region that dominates. It has two CFG predecessors and only dominates one of them. Thus, it lies one CFG edge outside the region that dominates. In general, a definition of in some block will necessitate a -function in any node that, like , lies one CFG edge beyond the region that dominates. The dominance frontier of , denoted DF(), is the set of all such nodes.

Dominance frontier In a CFG, node is in the dominance frontier of node p if and only if (1) p dominates a CFG predecessor of and (2) p does not strictly dominate . We denote p 's dominance frontier as .

To recap, DF() if, along some path, is one edge beyond the region that dominates. Thus:

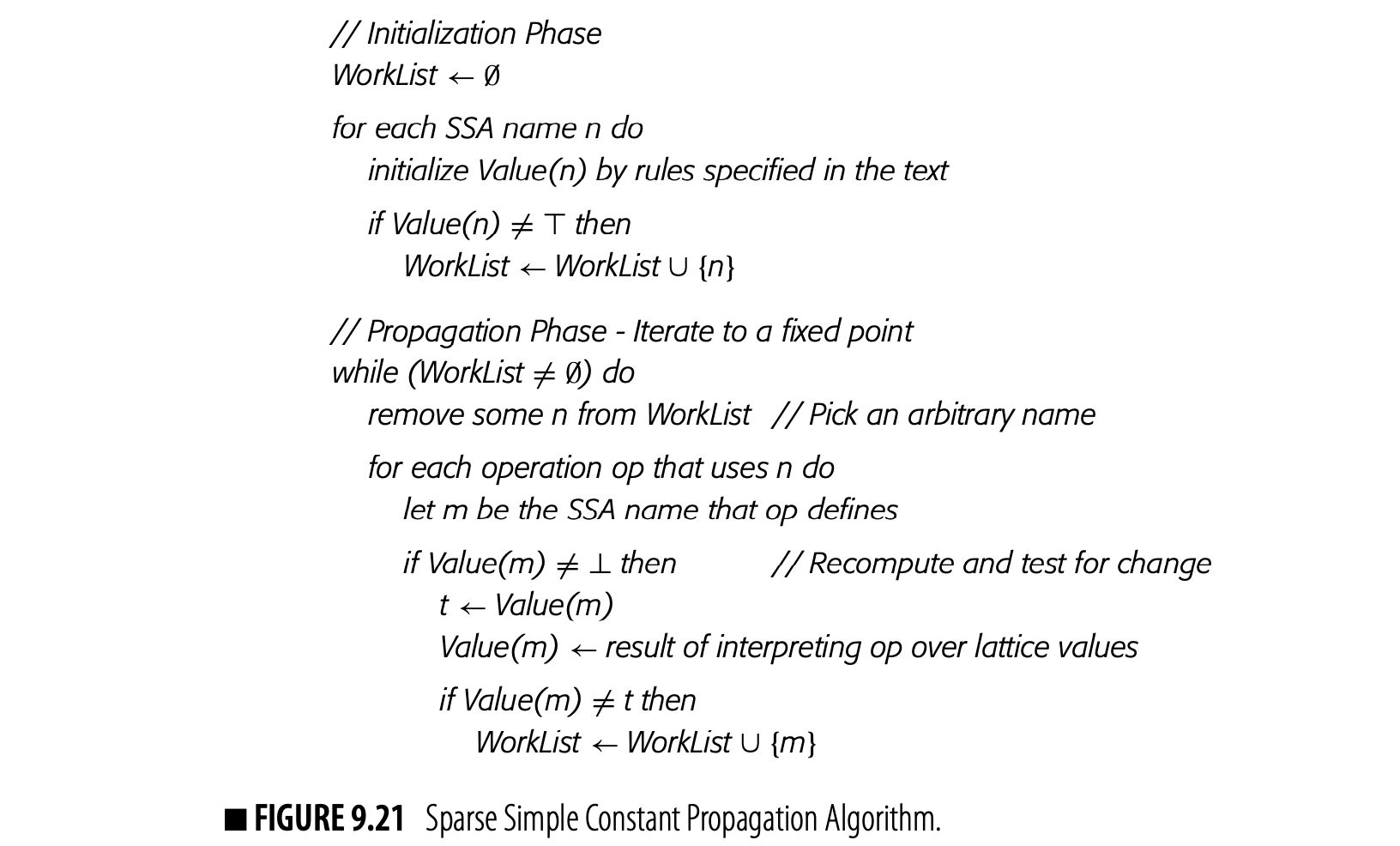

- has a CFG predecessor that dominates. There exists an such that is a CFG edge and .

- does not strictly dominate . That is, .

DF() is simply the set of all nodes that meet these two criteria.

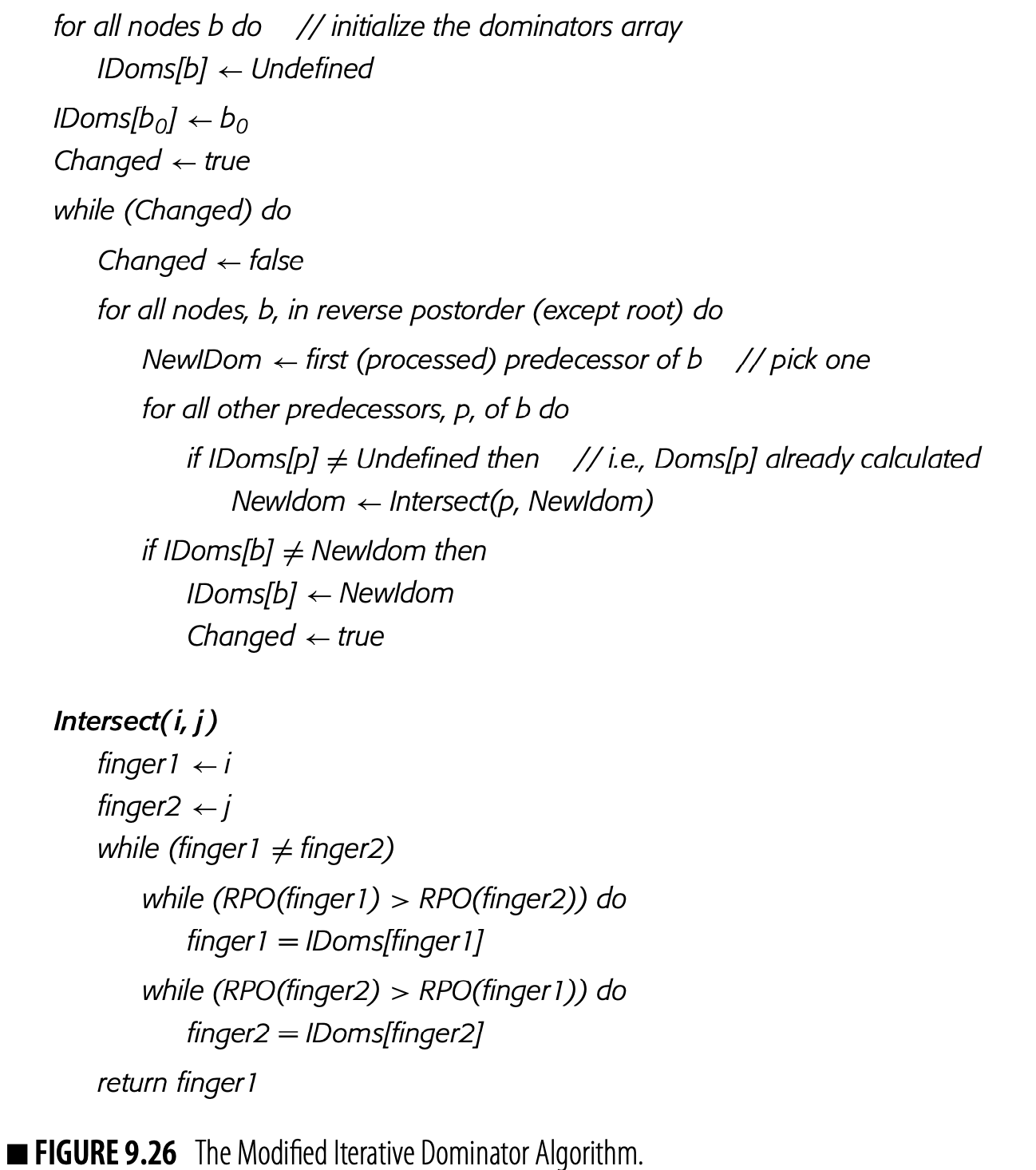

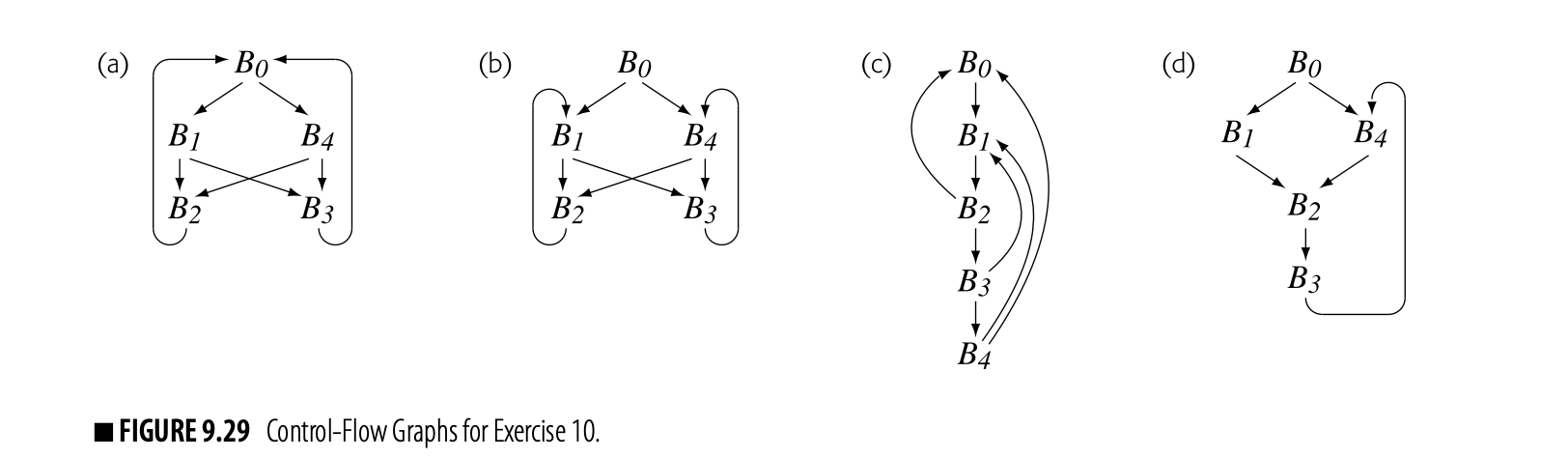

A definition of in block forces the insertion of a -function for at the head of each block DF(). Fig. 9 shows the Dom, IDom, and DF sets for the example CFG.

Notice the role of strict dominance. In the example CFG, strict dominance ensures that DF(). Thus, an assignment to some name in forces

the insertion of a -function in . If the definition of dominance frontiers used Dom, instead, would be empty.

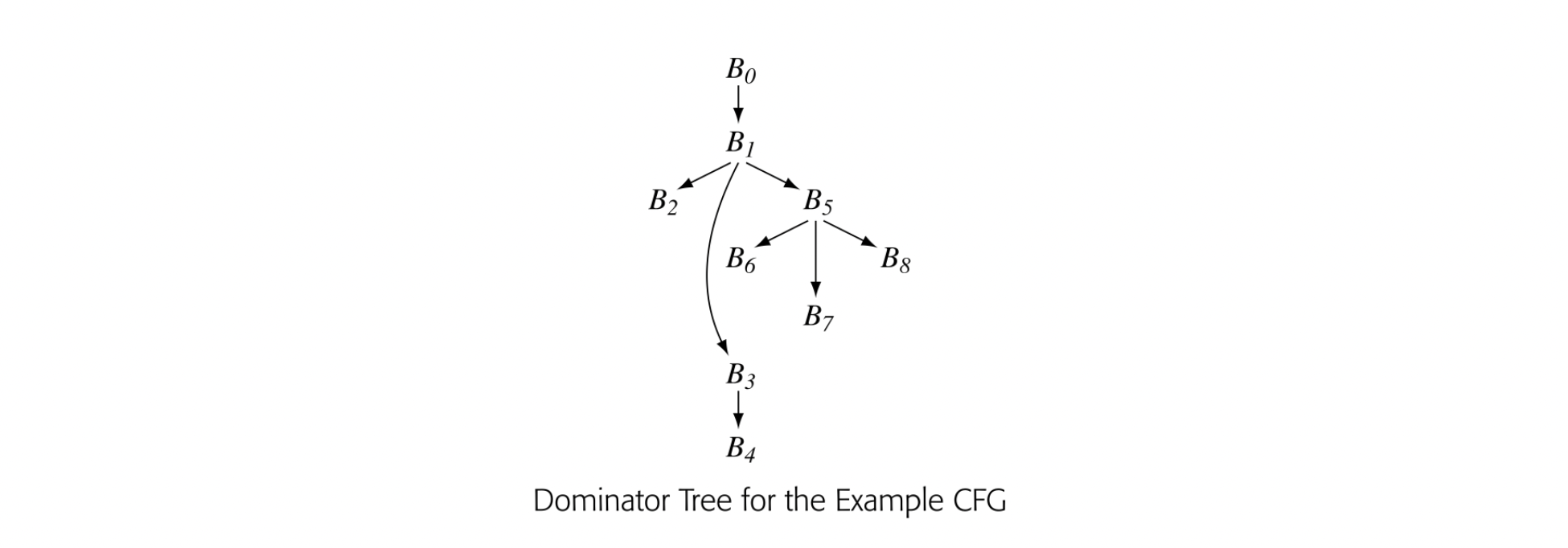

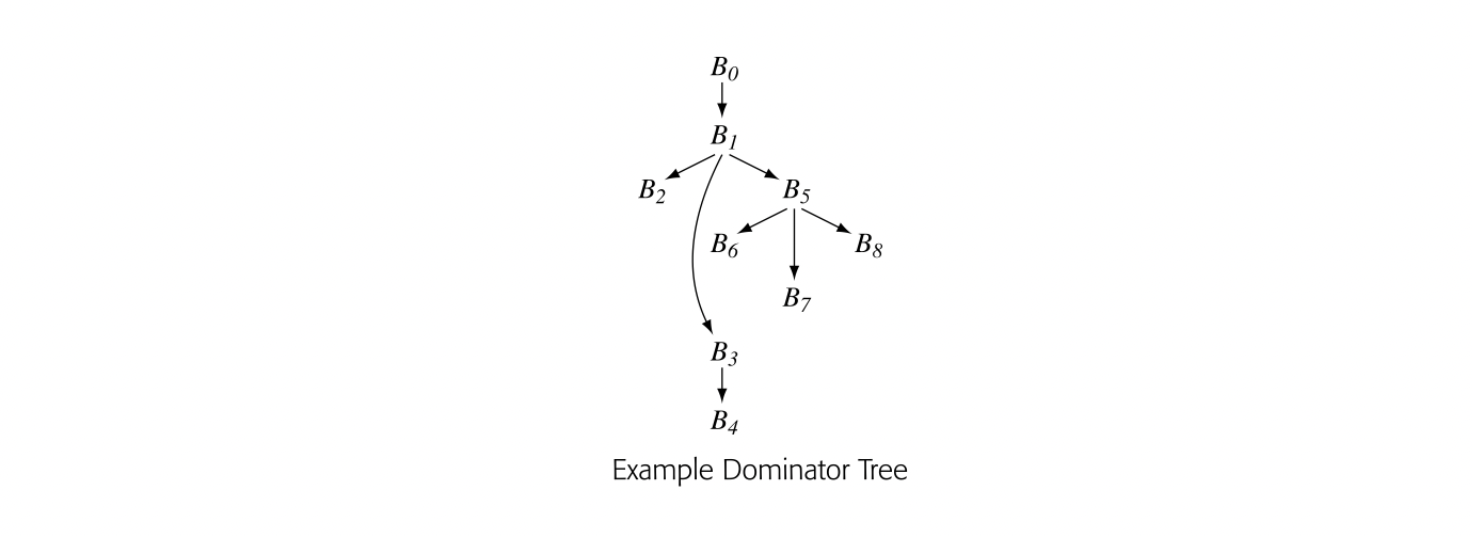

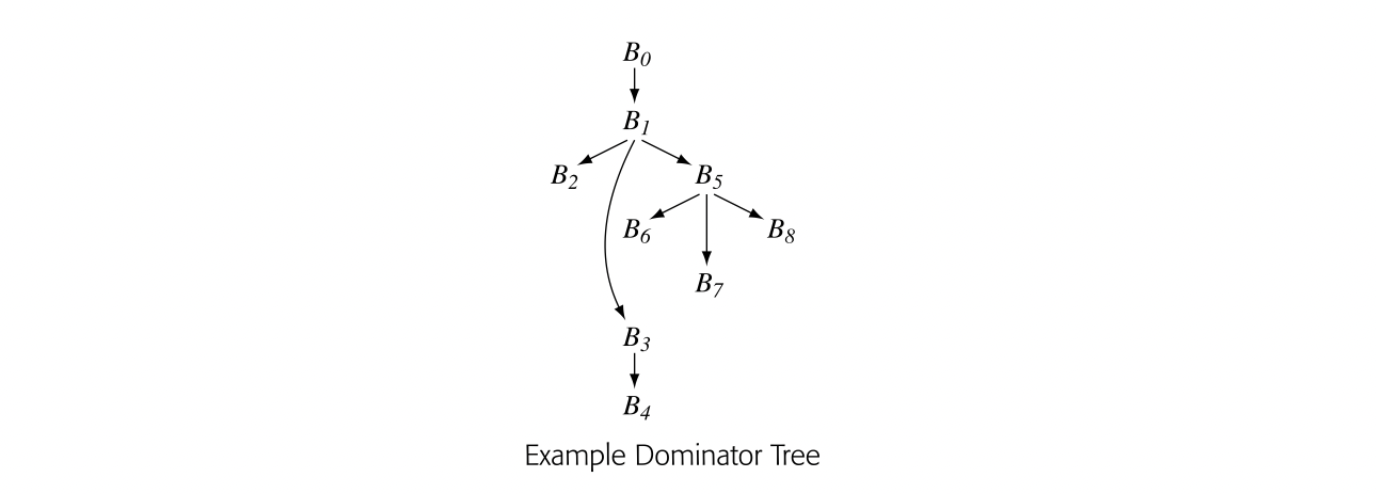

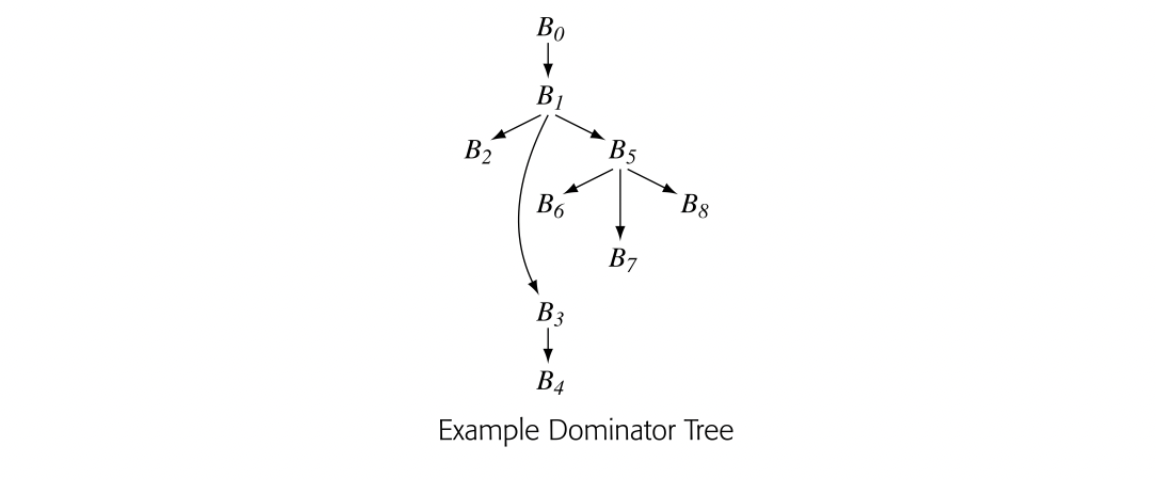

Dominator Trees

Dominator tree a tree that encodes the dominance informa- tion for a flow graph

The algorithm to compute dominance frontiers uses a data structure, the dominator tree, to encode dominance relationships. The dominator tree of a CFG has a node for each block in the CFG. Edges encode immediate dominance; if , then is a child of in the dominator tree.

The dominator tree encodes the Dom sets as well. For a node , contains precisely the nodes on the path from to the root of the dominator tree. The nodes on that path are ordered by the IDom relationship. The dominator tree for our running example appears in the margin.

Computing Dominance Frontiers

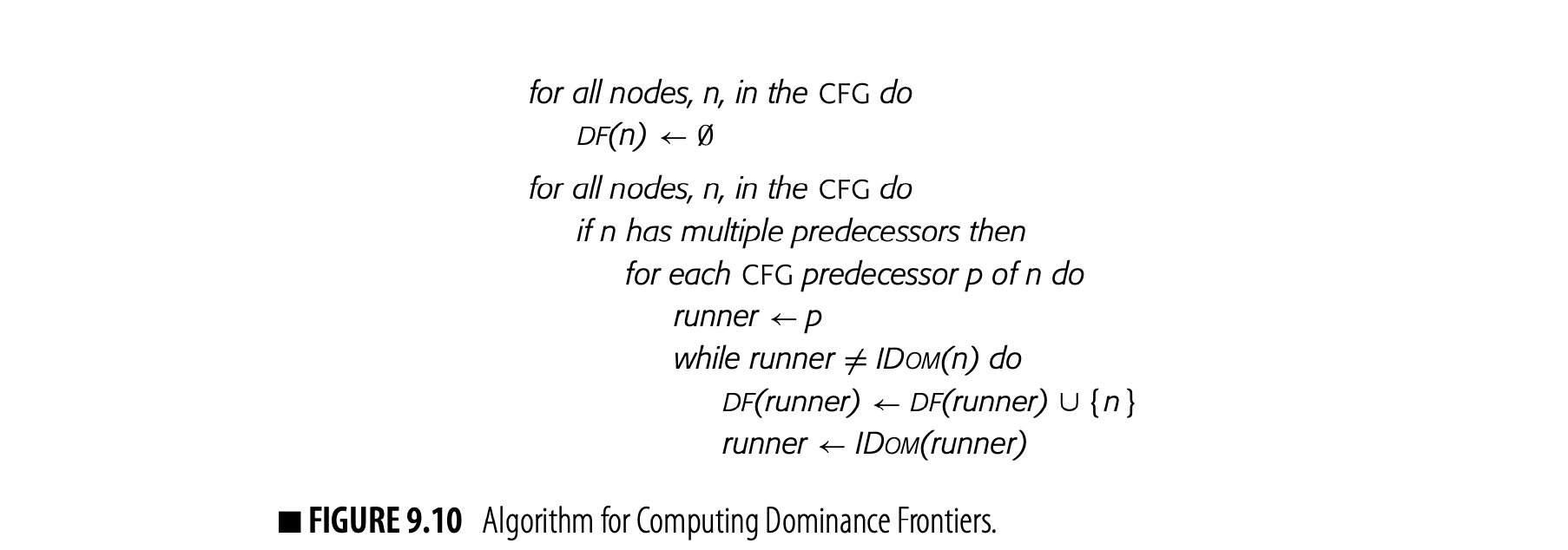

To make -insertion efficient, the compiler should precompute, for each CFG node , a set that contains 's dominance frontier. The algorithm, shown in Fig. 9.10, uses both the dominator tree and the CFG to build the sets.

Notice that the DF sets can only contain nodes that are join points in the CFG--that is, nodes that have multiple predecessors. Thus, the algorithm starts with the join points. At a CFG join point , it iterates over 's CFG predecessors and inserts into as needed.

If , then p also dominates all of n 's other predecessors. In the example, .

- If , then does not belong to . Neither does it belong to for any predecessor of .

- If , then belongs in . It also belongs in for any such that and . The algorithm finds these latter nodes by running up the dominator tree.

The algorithm follows from these observations. It initializes to , for all CFG nodes . Next, it finds each CFG join point and iterates over 's

CFG predecessors, . If dominates , the algorithm is done with . If not, it adds to DF() and walks up the dominator tree, adding to the DF set of each dominator-tree ancestor until it finds 's immediate dominator. The algorithm needs a small amount of bookkeeping to avoid adding to a DF set multiple times.

Consider again the example CFG and its dominator tree. The analyzer examines the nodes in some order, looking for nodes with multiple predecessors. Assuming that it takes the nodes in name order, it finds the join points as , then , then .

Consider again the example CFG and its dominator tree. The analyzer examines the nodes in some order, looking for nodes with multiple predecessors. Assuming that it takes the nodes in name order, it finds the join points as , then , then .

- For CFG-predecessor , the algorithm finds that is IDom(), so it never enters the while loop. For CFG-predecessor , it adds to DF() and sets to IDom() = . It adds to DF() and sets to IDom() = , where it halts.

- For CFG-predecessor , it adds to DF() and sets to IDom() = . Since = IDom(), it halts. For CFG-predecessor , it adds to DF() and sets to IDom() = . It adds to DF() and sets to IDom() = , where it halts.

- For CFG-predecessor , it adds to DF() and advances to IDom() = , where it halts. For CFG-predecessor , it adds to DF() and advances to IDom() = , where it halts.

These results produce the DF sets shown in the table in Fig. 9.9.

9.3.3 Placing -Functions

The naive algorithm placed a -function for every variable at the start of every join node. With dominance frontiers, the compiler can determine more precisely where -functions might be needed. The basic idea is simple.

- From a control-flow perspective, an assignment to in CFG node induces a -function in every CFG node m\in\mbox{DF}(n). Each inserted -function creates a new assignment; that assignment may, in turn, induce additional -functions.

- From a data-flow perspective, a -function is only necessary if its result is live at the point of insertion. The compiler could compute live information and check each -function on insertion; that approach leads to pruned SSA form.

The word is used here to mean of interest across the entire procedure.

In practice, the compiler can avoid most dead -functions with an inexpensive approximation to liveness. A name cannot need a -function unless it is live in multiple blocks. The compiler can compute the set of global names--those that are live in multiple blocks. The SSA-construction can ignore any nonglobal name, which reduces the name space and the number of -functions. The resulting SSA form is called .

The compiler can find the global names cheaply. In each block, it looks for names with upward-exposed uses--the UEVar set from the live-variables calculation. Any name that appears in a LiveOut set must be in the UEVar set of some block. Taking the union of all the UEVar sets gives the compiler the set of names that are live on entry to one or more blocks and, hence, live in multiple blocks.

The algorithm to find global names, shown in Fig. 11(a), is derived from the obvious algorithm for computing UEVar. It constructs both a set of global names, Globals, and, for each name, the set of blocks that contain a definition of that name. The algorithm uses these block lists to form initial worklists during -function insertion.

The algorithm for inserting -functions, in panel (b), iterates over the global names. For each name , it initializes WorkList with Blocks(). For each block in WorkList, it inserts a -function at the head of each block in 's dominance frontier. The parallel execution semantics of the -functions lets the algorithm insert them at the head of in any order. When it adds a -function for to , the algorithm adds to WorkList to reflect the new assignment to in .

Example

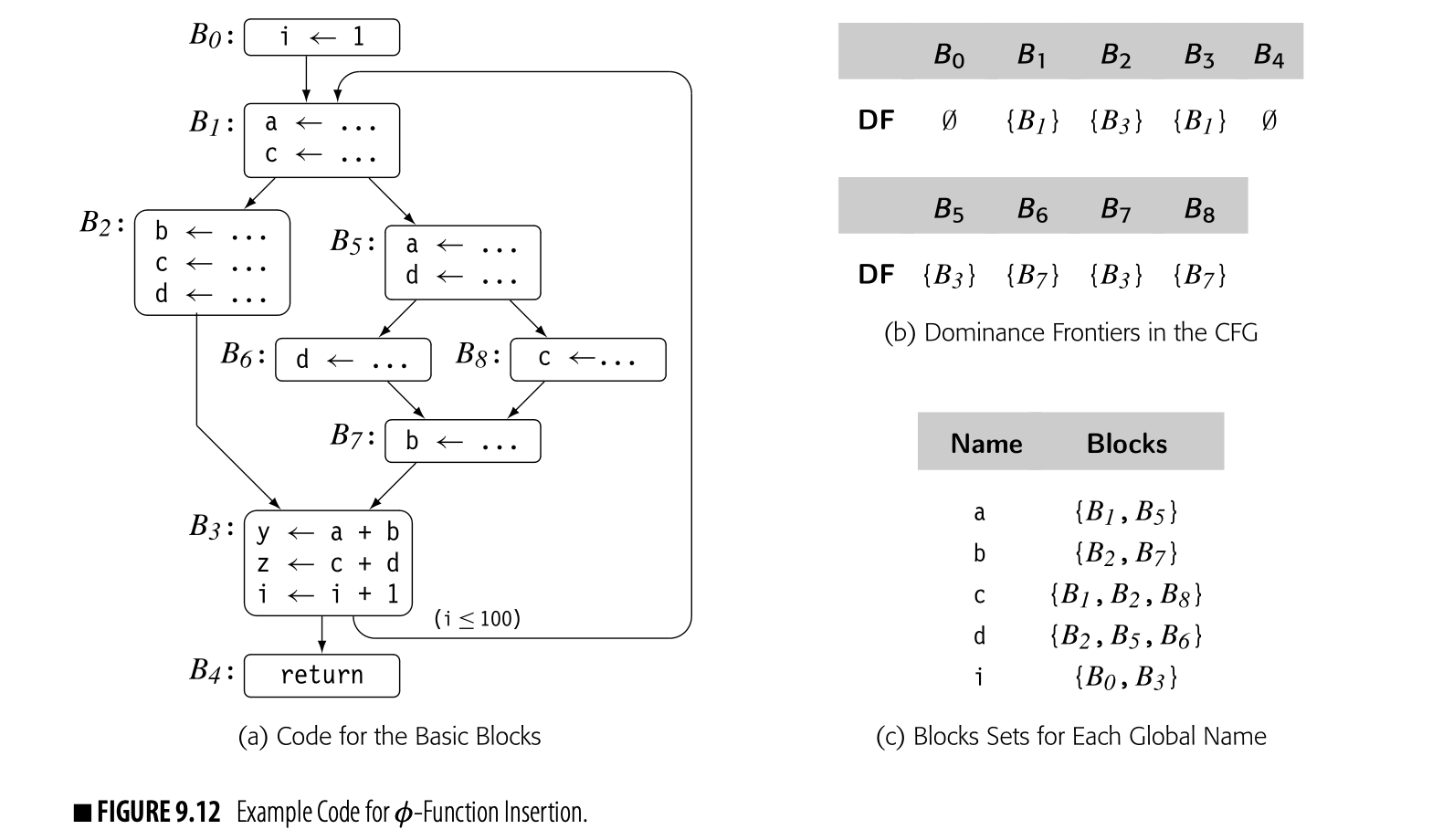

Fig. 9.12 recaps our running example. Panel (a) shows the code and panel (b) shows the dominance frontiers for the CFG.

The compiler could avoid computing Blocks sets for nonglobal names, at the cost of another pass over the code.

The first step in the -function insertion algorithm finds global names and computes the set for each name. The global names are . The sets for the global names are shown in panel (c). While the algorithm computes a set for each of y and z, the table omits them because they are not global names.

The -function insertion algorithm, shown in Fig. 9.11(b), works on a name-by-name basis. Consider its actions for the variable a in the example. First, it initializes the worklist to , to denote the fact that a is defined in and .

The definition of a in causes insertion of a -function for a at the start of each block in . The -function in is a new assignment, so the algorithm adds to . Next, the algorithm removes from the worklist and inserts a -function in each block of . The new -function in causes the algorithm to add to the worklist. When comes off the worklist, the algorithm discovers that the -function induced by in already exists. It neither adds a duplicate -function nor adds blocks to . When comes off the worklist, the algorithm also finds the -function for a in . At that point, is empty and the processing for a halts.

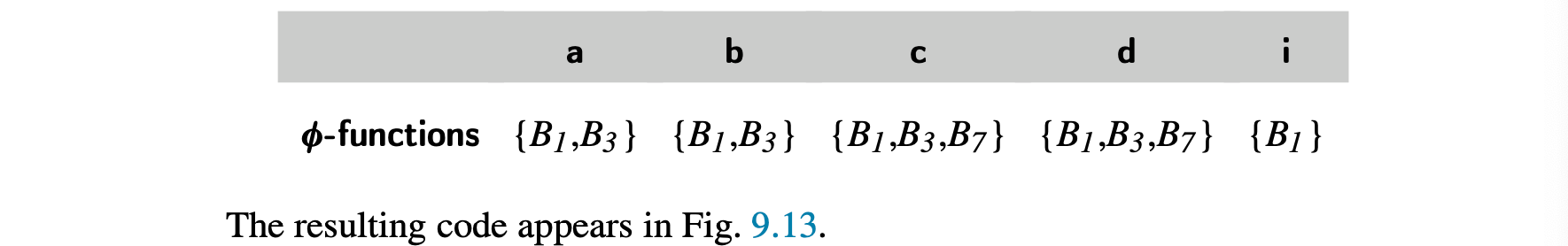

The algorithm follows the same logic for each name in Globols, to produce the following insertions:

Limiting the algorithm to global names keeps it from inserting dead -functions for and in block . ( and defines both and .) However, the distinction between local names and global names is not sufficient to avoid all dead -functions. For example, the -function for b in is not live because b is redefined before its value is used. To avoid inserting these -functions, the compiler can construct LiveOut sets and add a test based on liveness to the inner loop of the -function insertion algorithm. That modification causes the algorithm to produce .

Efficiency Improvements

To improve efficiency, the compiler should avoid two kinds of duplication. First, the algorithm should avoid placing any block on the worklist more than once per global name. It can keep a checklist of blocks that have already been processed for the current name and reset the checklist when it starts to process a new name.

Both of these checklists can be imple- mented as sparse sets (see Appendix B.2.3).

Second, a given block can be in the dominance frontier of multiple nodes that appear on the WorkList. The algorithm must check, at each insertion, for a preexisting -function for the current name. Rather than searching through the -functions in the block, the compiler should maintain a checklist of blocks that already contain -functions for the current variable. Again, this checklist must be reset when the algorithm starts to process a new name.

9.3.4 Renaming

Earlier, we stated that the algorithm for renaming variables was conceptually straightforward. The details, however, require explanation.

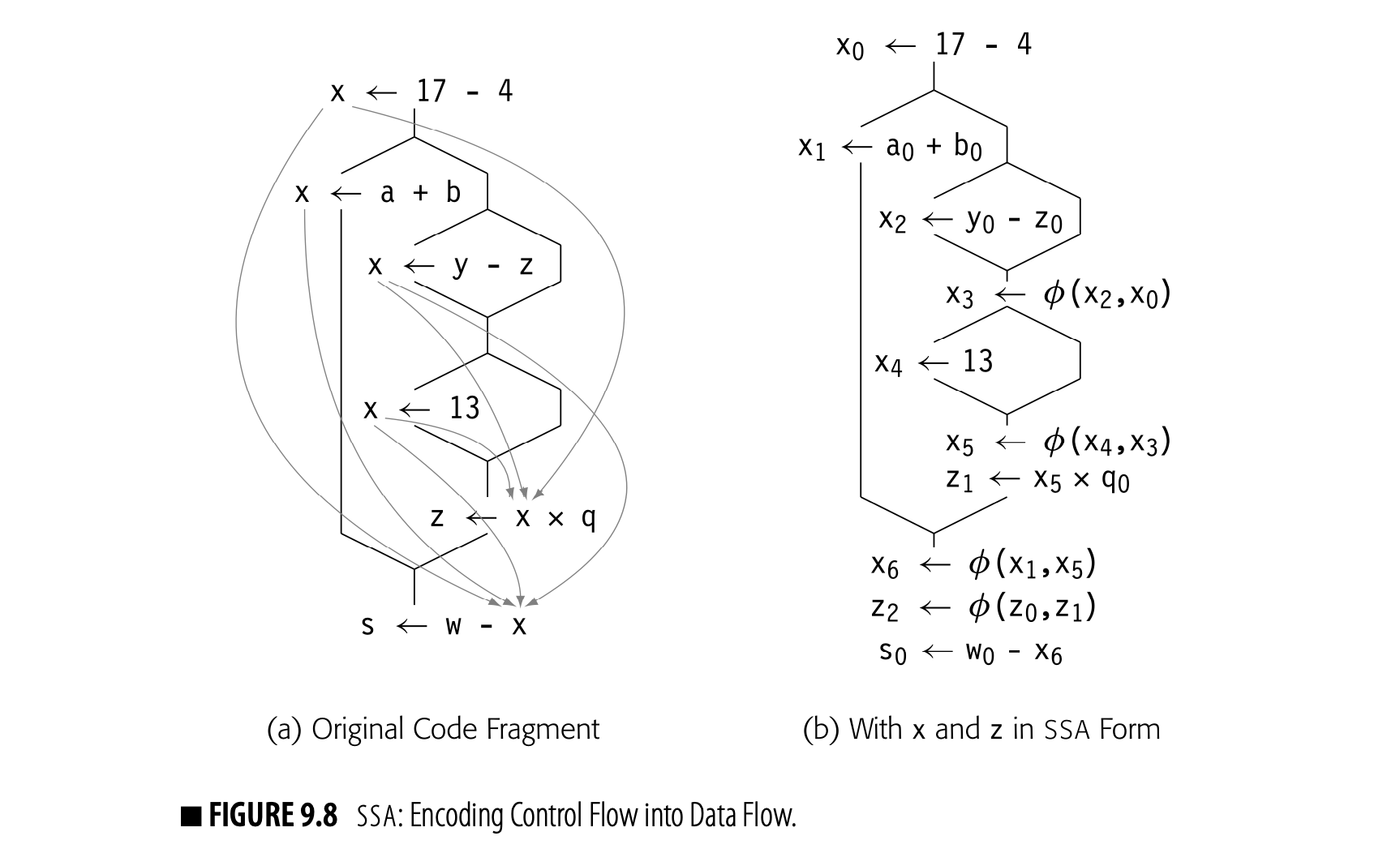

In the final SSA form, each global name becomes a base name, and individual definitions of that base name are distinguished by the addition of a numerical subscript. For a name that corresponds to a source-language variable, say a, the algorithm uses a as the base name. Thus, the first definition of a that the renaming algorithm encounters will be named a0 and the second will be a1. For a compiler-generated temporary, the algorithm can use its pre-SSA name as its base name.

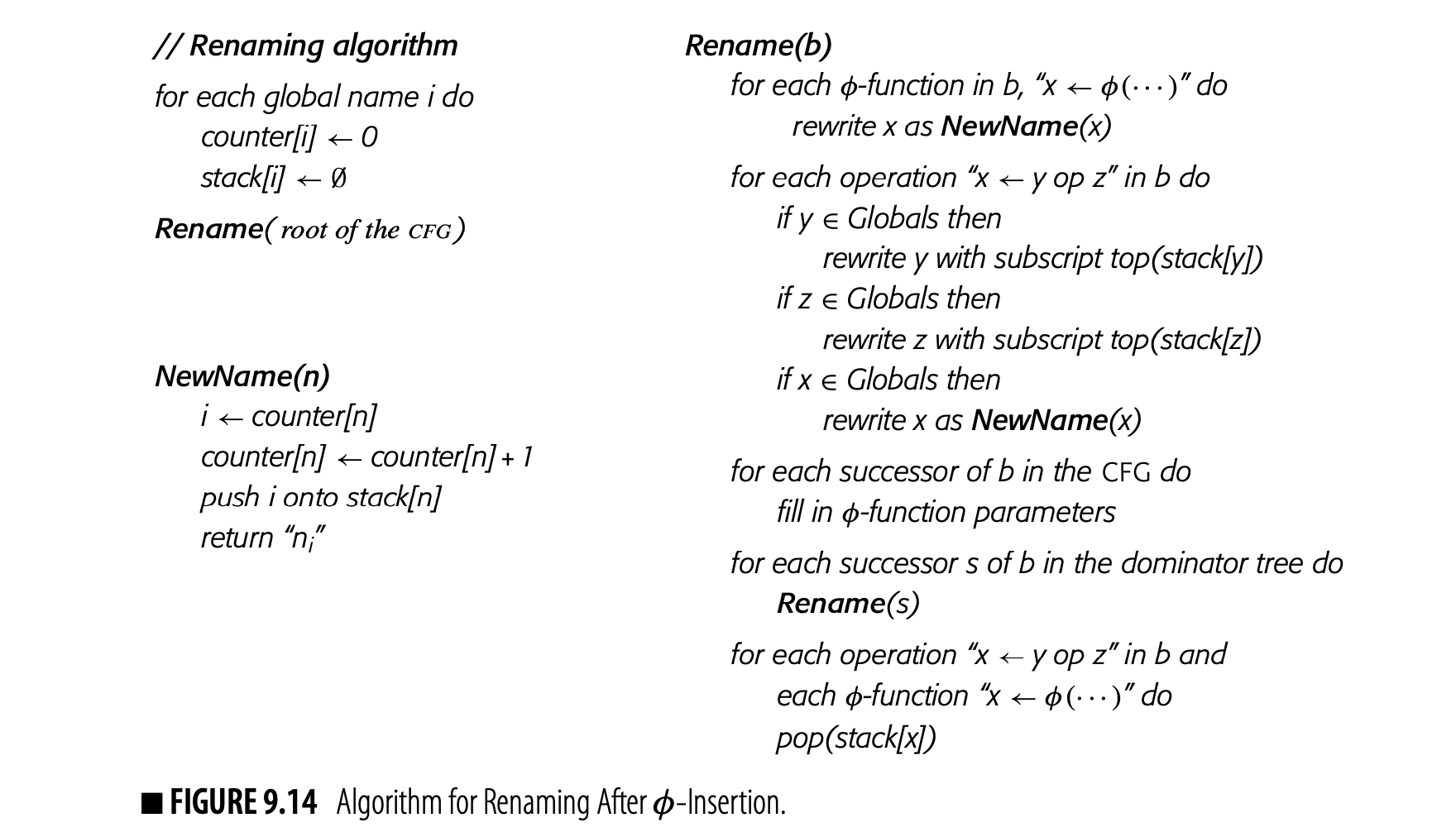

The algorithm, shown in Fig. 14, renames both definitions and uses in a preorder walk over the procedure's dominator tree. In each block, it first renames the values defined by -functions at the head of the block. Next, it visits each operation in the block, in order. It rewrites the operands with current SSA names and then creates a new SSA name for the result of the operation. This latter act makes the new name current. After all the operations in the block have been rewritten, the algorithm rewrites the appropriate -function parameters in each CFG successor of the block, using the current SSA names. Finally, it recurs on any children of the block in the dominator tree. When it returns from those recursive calls, it restores the set of current SSA names to the state that existed before the current block was visited.

To manage the names, the algorithm uses a counter and a stack for each global name. A name's stack holds the subscript from its current SSA name. At each definition, the algorithm generates a new subscript for the defined base name by pushing the value of its current counter onto the stack and incrementing the counter. Thus, the value on top of the stack for is always the subscript of 's current SSA name.

As the final step, after recurring on the block's children in the dominator tree, the algorithm pops all the names generated in that block off their respective stacks. This action reveals the names that held at the end of that block's immediate dominator. Those names may be needed to process the block's remaining dominator-tree siblings.

The stack and the counter serve distinct and separate purposes. As the algorithm moves up and down the dominator tree, the stack is managed to simulate the lifetime of the most recent definition in the current block. The counter, on the other hand, grows monotonically to ensure that each successive definition receives a unique SSA name.

Fig. 9.14 summarizes the algorithm. It initializes the stacks and counters, then calls Rename on the dominator tree's root--the CFG's entry node. Rename processes the block, updates -function arguments in its CFG successor blocks, and recurs on its dominator-tree successors. To finish the block, Rename pops off the stacks any names that it added as it processed the block. The function NewName manipulates the counters and stacks to create new SSA names as needed.

One final detail remains. When Rename rewrites the -function parameters in each of 's CFG successors, it needs a mapping from to an ordinal parameter slot in those -functions for . That is, it must know which parameter slot in the -functions corresponds to .

When we draw SSA form, we assume a left-to-right order that matches the left-to-right order in which the edges are drawn. Internally, the compiler can number the edges and parameter slots in any consistent fashion that produces the desired result. This requires cooperation between the code that builds SSA and the code that builds the CFG. (For example, if the CFG implementation uses a list of edges leaving each block, the order of that list can determine the mapping.)

Example

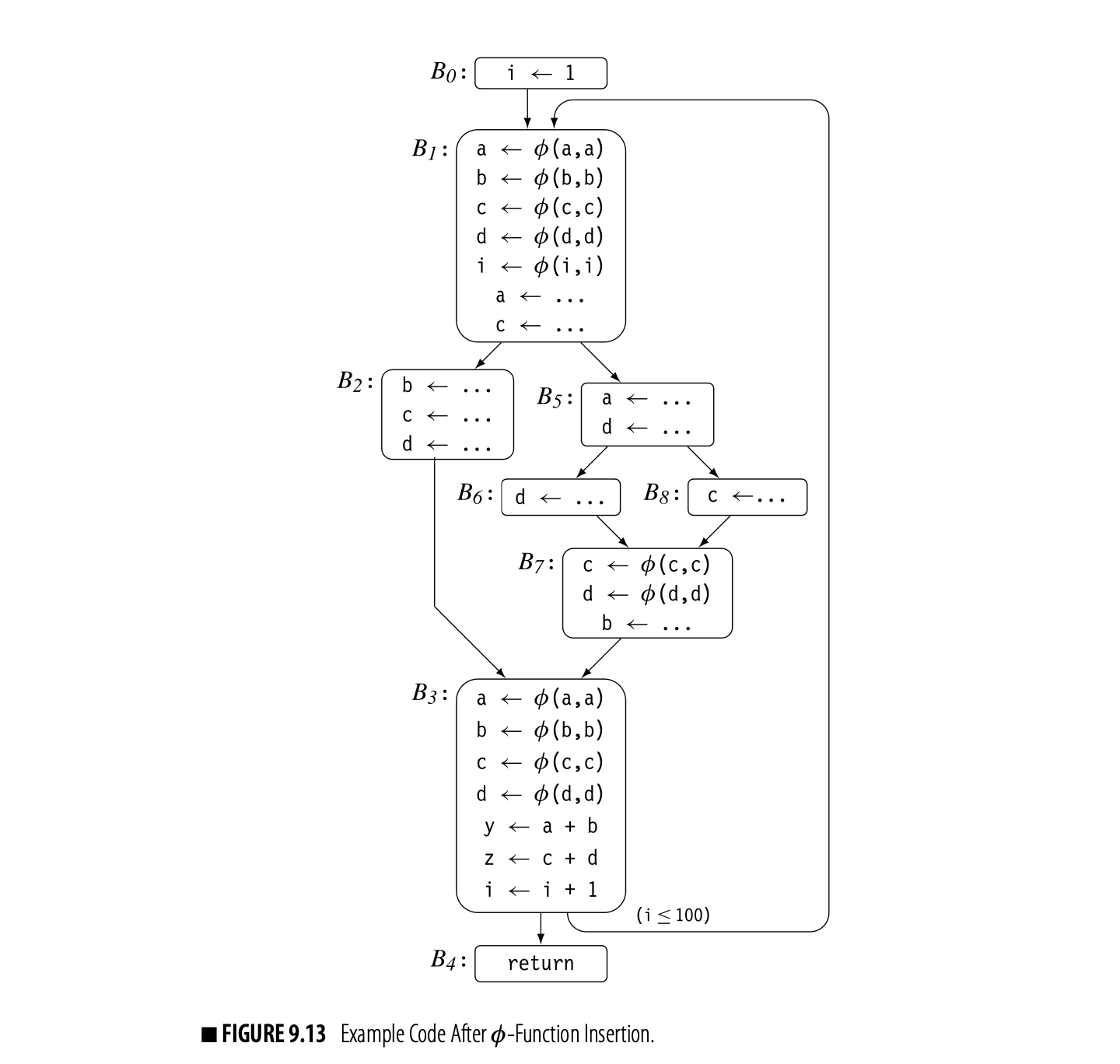

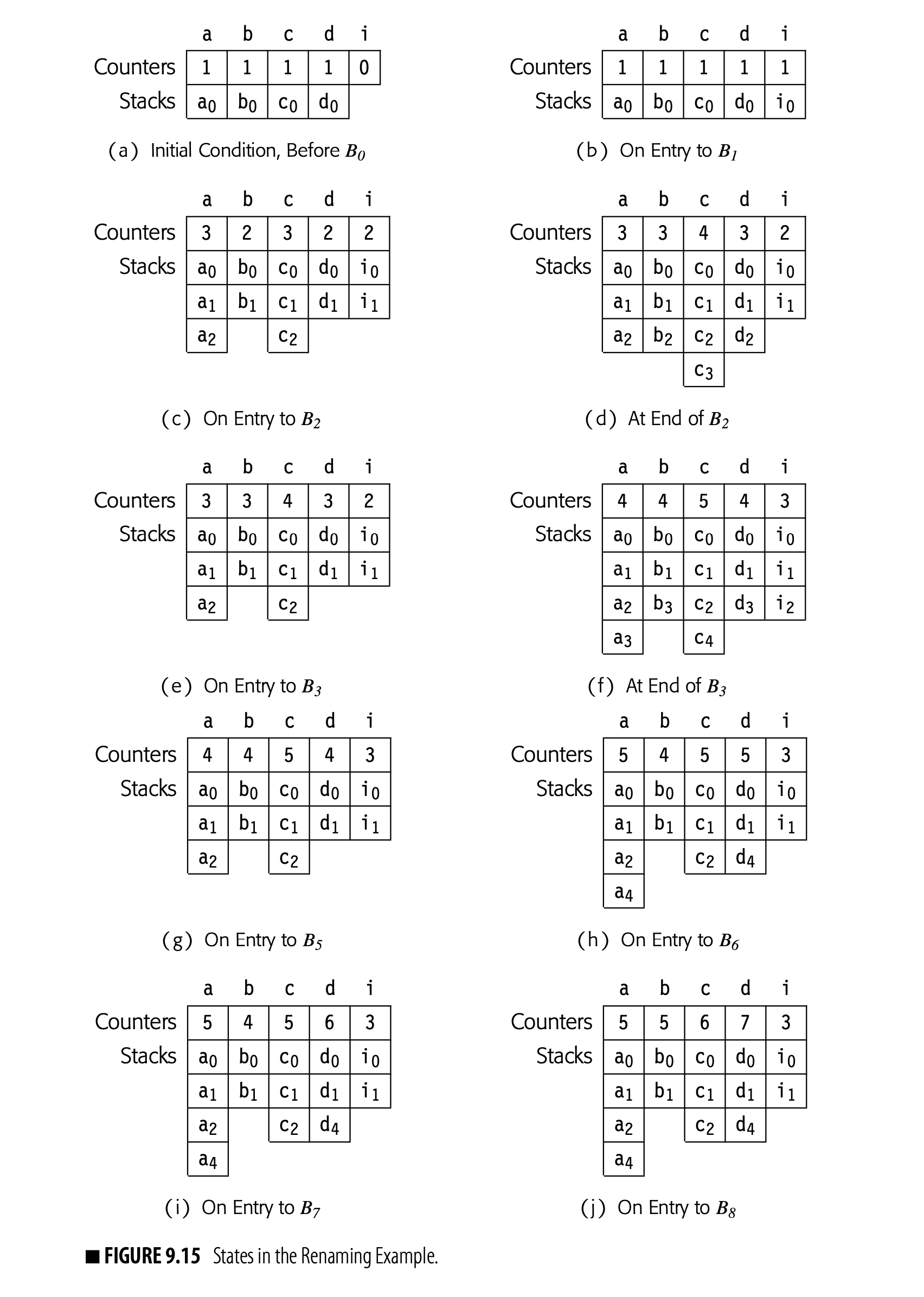

To finish the continuing example, let's apply the renaming algorithm to the code in Fig. 9.13. Assume that , , , and are defined on entry to . Fig. 9.15 shows the states of the counters and stacks for global names at various points during the process.

The algorithm makes a preorder walk over the dominator tree, which, in this example, corresponds to visiting the nodes in ascending order by name. Fig. 9.15(a) shows the initial state of the stacks and counters. As the algorithm proceeds, it takes the following actions:

Block This block contains only one operation. Rename rewrites with , increments 's counter, and pushes onto the stack for . Next, it visits 's CFG-successor, , and rewrites the -function parameters that correspond to with their current names: , , , , and . It then recurs on 's child in the dominator tree, . After that, it pops the stack for and returns.

Block Rename enters with the state shown in panel (b). It rewrites the -function targets with new names, , , , , and . Next, it creates new names for the definitions of and and rewrites them. Neither of 's CFG successors have -functions, so it recurs on 's dominator-tree children, , , and . Finally, it pops the stacks and returns.

Block Rename enters with the state shown in panel (c). This block has no -functions to rewrite. Rename rewrites the definitions of , , and , creating a new SSA name for each. It then rewrites -function parameters in 's CFG successor, . Panel (d) shows the stacks and counters just before they are popped. Finally, it pops the stacks and returns.

Block B3 Rename enters with the state shown in panel (e). Notice that the stacks have been popped to their state when Rename entered , but the counters reflect the names created inside . In , Rename rewrites the -function targets, creating new SSA names for each. Next, it rewrites each assignment in the block, using current SSA names for the uses of global names and then creating new SSA names for definitions of global names. has two CFG successors, and . In , it rewrites the -function parameters that correspond to the edge from , using the stacks and counters shown in panel (f). has no -functions. Next, Rename recurs on 's dominator-tree child, . When that call returns, Rename pops the stacks and returns.

Block B4 This block just contains a return statement. It has no -functions, definitions, uses, or successors in either the CFG or the dominator tree. Thus, Rename performs no actions and leaves the stacks and counters unchanged.

Block B5 After , Rename pops through back to . With the stacks as shown in panel (g), it recurs down into 's final dominator-tree child, . has no -functions. Rename rewrites the two assignment statements, creating new SSA names as needed. Neither of 's CFG successors has -functions. Rename next recurs on 's dominator-tree children, , , and . Finally, it pops the stacks and returns.

Block B6 Rename enters with the state in panel (h). has no -functions. Rename rewrites the assignment to d, generating the new SSA name d5. Next, it visits the -functions in 's CFG successor . It rewrites the -function arguments along the edge from with their current names, and d5. Since has no dominator-tree children, it pops the stack for d and returns.

Block B7 Rename enters with the state shown in panel (i). It first renames the -function targets with new SSA names, and d6. Next, it rewrites the assignment to b with new SSA name b4. It then rewrites the -function arguments in 's CFG successor, , with their current names. Since has no dominator-tree children, it pops the stacks and returns.

Block B7 Rename enters with the state shown in panel (i). It first renames the -function targets with new SSA names, and d6. Next, it rewrites the assignment to b with new SSA name b4. It then rewrites the -function arguments in 's CFG successor, , with their current names. Since has no dominator-tree children, it pops the stacks and returns.

Block B8: Rename enters with the state shown in panel (j). has no -functions. Rename rewrites the assignment to c with new SSA name c6. It rewrites the appropriate -function arguments in with their current names, and d4. Since has no dominator-tree children, it pops the stacks and returns.

Fig 9.16 shows the code after Rename halts.

A Final Improvement

We can reduce the time and space spent in stack manipulation with a clever implementation of NewName. The primary use of the stacks is to reset the name space on exit from a block. If a block redefines the same base name multiple times, the stack only needs to keep the most recent name. For example, in block , both a and c are defined twice. NewName could reuse the slots for a and c when it creates a and c.

With this change, Rename performs one push and one pop per base name defined in the block. NewName can keep a list of the stack entries that it creates; on exit from the block, Rename can then walk the list to pop theappropriate stacks. The stacks require less space; their size is bounded by the depth of the dominator tree. Stack manipulation is simplified; the algorithm performs fewer push and pop operations and the push operation need not test for a stack overflow.

9.3.5 Translation out of SSA Form

Actual processors do not implement φ- functions, so the compiler must rewrite the code without the φ-functions.

A compiler that uses SSA form must translate that form of the code back into a more conventional model--one without -functions--before the code can execute on conventional computer hardware. The compiler must replace the -functions with copy operations and place them in the code so that they reproduce the semantics of those -functions: both the control-based selection of values and the parallel execution at the start of the block.

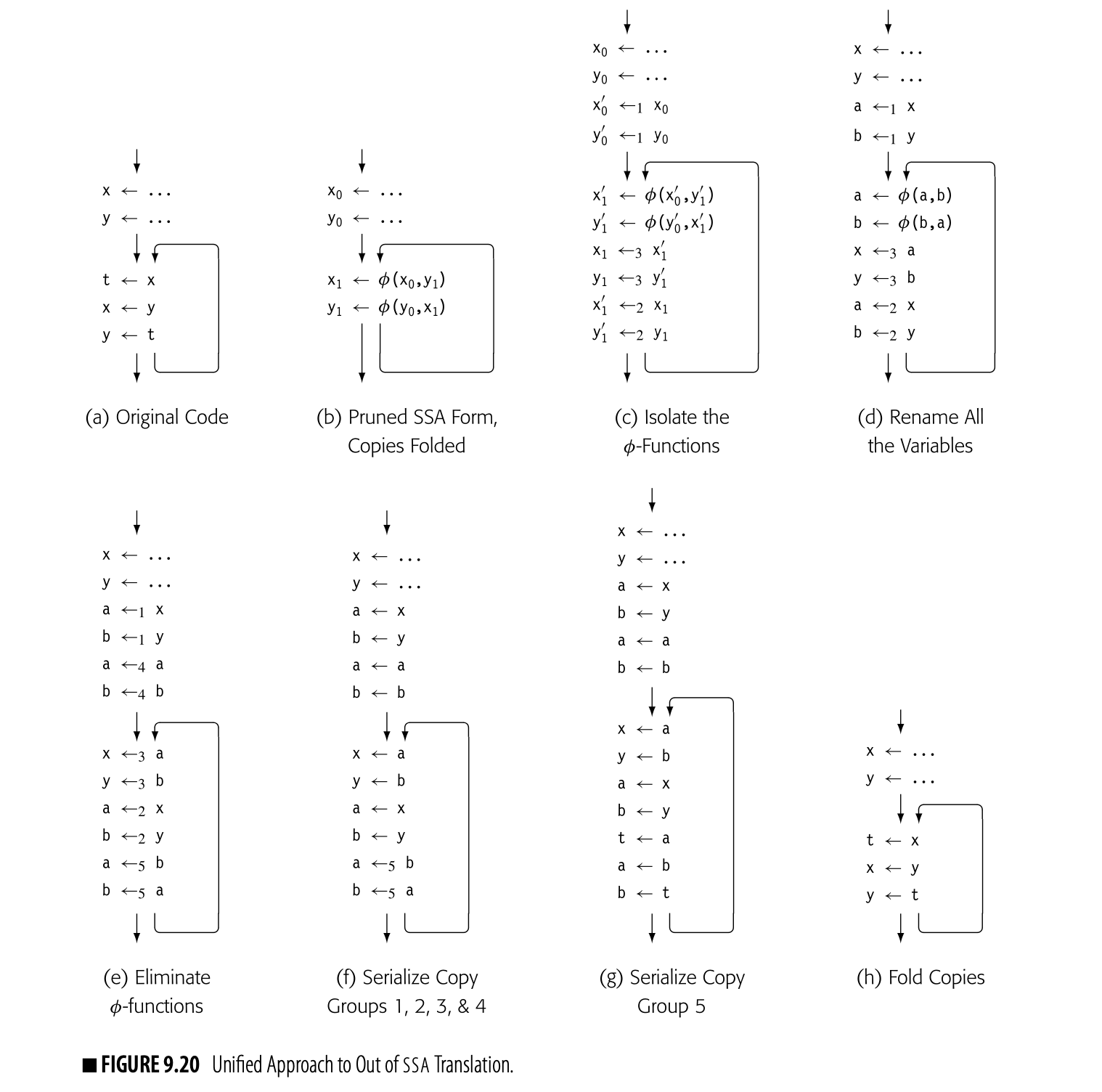

This section addresses out-of-SA translation. It begins with an overly simple, or naive, translation, which informs and motivates the actual translation schemes. Next, it presents two example problems that demonstrate the problems that can arise in translating from SSA form back to conventional code. Finally, it presents a unified framework that addresses the known complexities of the translation.

The Naive Translation

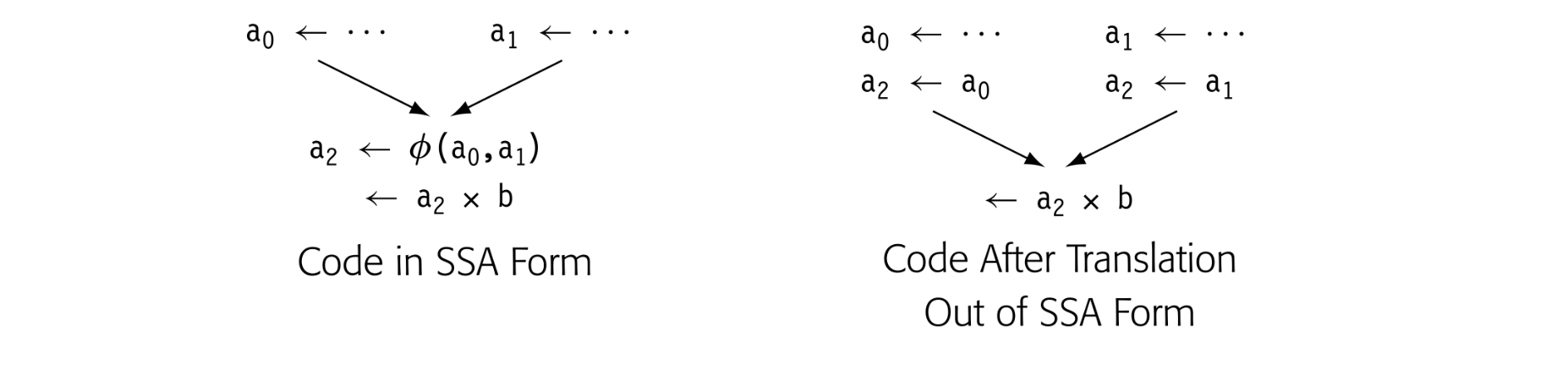

A -function is just a copy operation that selects its input based on prior control-flow. To replicate the effect of a -function at the top of block , the compiler can insert, at the end of each CFG-predecessor of , a copy operation that moves the appropriate -function argument into the name defined by the -function (shown in the margin). Once the compiler has inserted the copies, it can delete the -function.

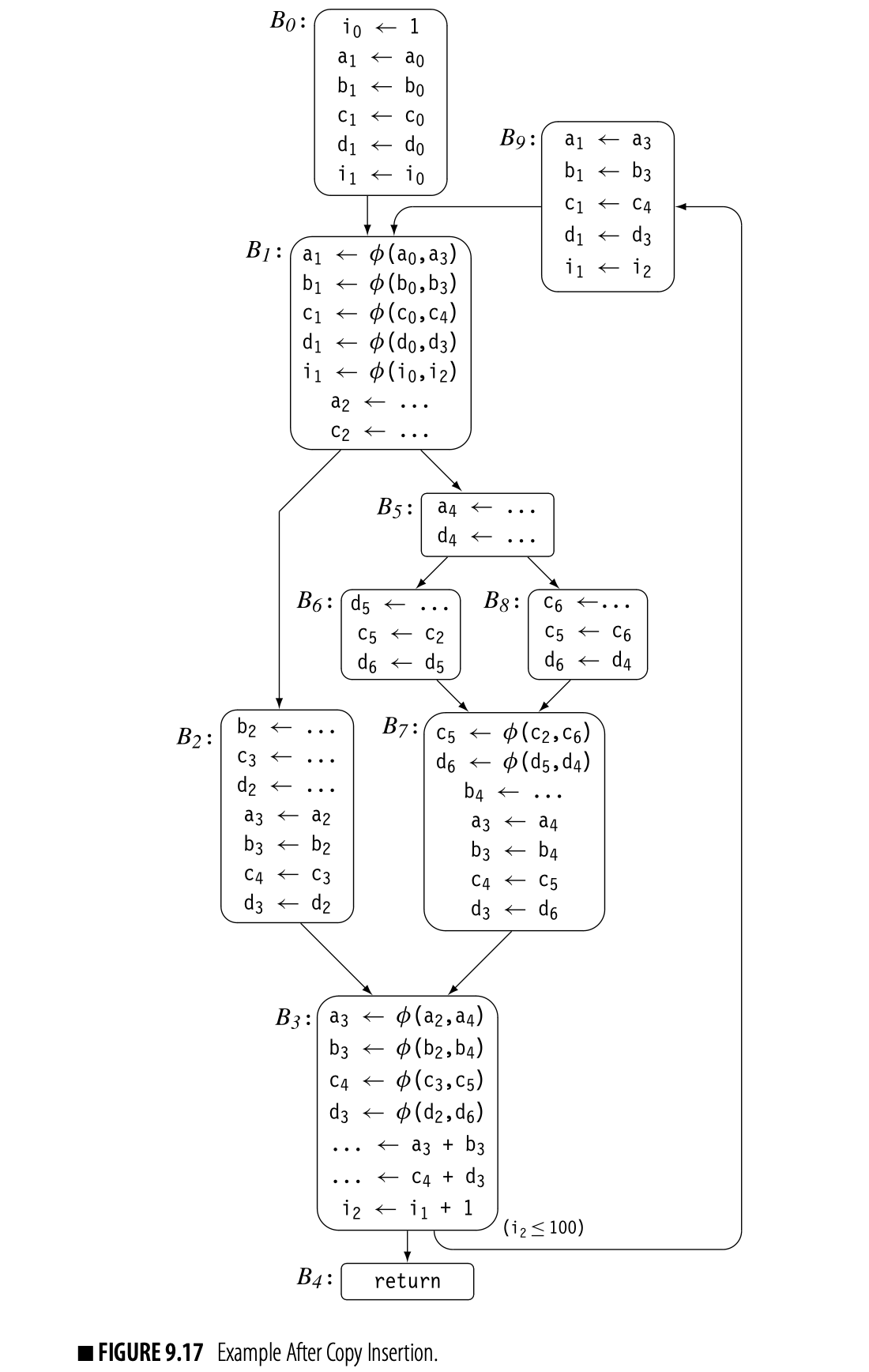

This process, while conceptually simple, has some complications. Consider, for example, the continuing example from Fig. 16. Three blocks in the CFG contain -functions: , , and . Fig. 17 shows the code after copies have been inserted.

For and , insertion into the predecessor blocks works. The predecessors of both and have one successor each, so the copy operations inserted at the end of those predecessor blocks have no effect on any path other than the one to the -function.

The situation is more complex for . Copy insertion at the end of 's predecessor, , produces the desired result; the copies only occur on the path . With 's other predecessor, , simple insertion will not work. A copy inserted at the end of will execute on both and . Along , the copy operation may change a value that is live in .

Critical edge A flow graph is a critical edge if has multiple successors and has multiple predecessors. Optimizations that move or insert code often need to split critical edges.

The edge highlights a more general problem with code placement on a critical edge. has multiple successors, so the compiler cannot insert the copy at the end of . has multiple predecessors, so the compiler cannot insert the copy at the start of . Since neither solution works, the compiler must split the edge and create a new block to hold the inserted copy operations. With the split edge and the creation of , the translated code faithfully reproduces the effects of the SSA form of the code.

Problems with the Naive Translation

If the compiler applies the naive translation to code that was produced directly by the translation into SSA form, the results will be correct, as long as critical edges can be split. If, however, the compiler transforms the code while it is in SSA form--particularly, transformations that move definitions or uses of SSA names--or if the compiler cannot split critical edges, then the naive translation can produce incorrect code. Two examples demonstrate how the naive translation can fail.

The Lost-Copy Problem

In Fig. 9.17, the compiler had to split the edge to create a location for the copy operations associated with that edge. In some situations, the compiler cannot or should not split a critical edge. For example, an SSA-based register allocator should not add any blocks or edges during copy insertion (see Section 13.5.3). The combination of an unsplit critical edge and an optimization that extends some SSA-name's live range can create a situation where naive copy insertion fails.

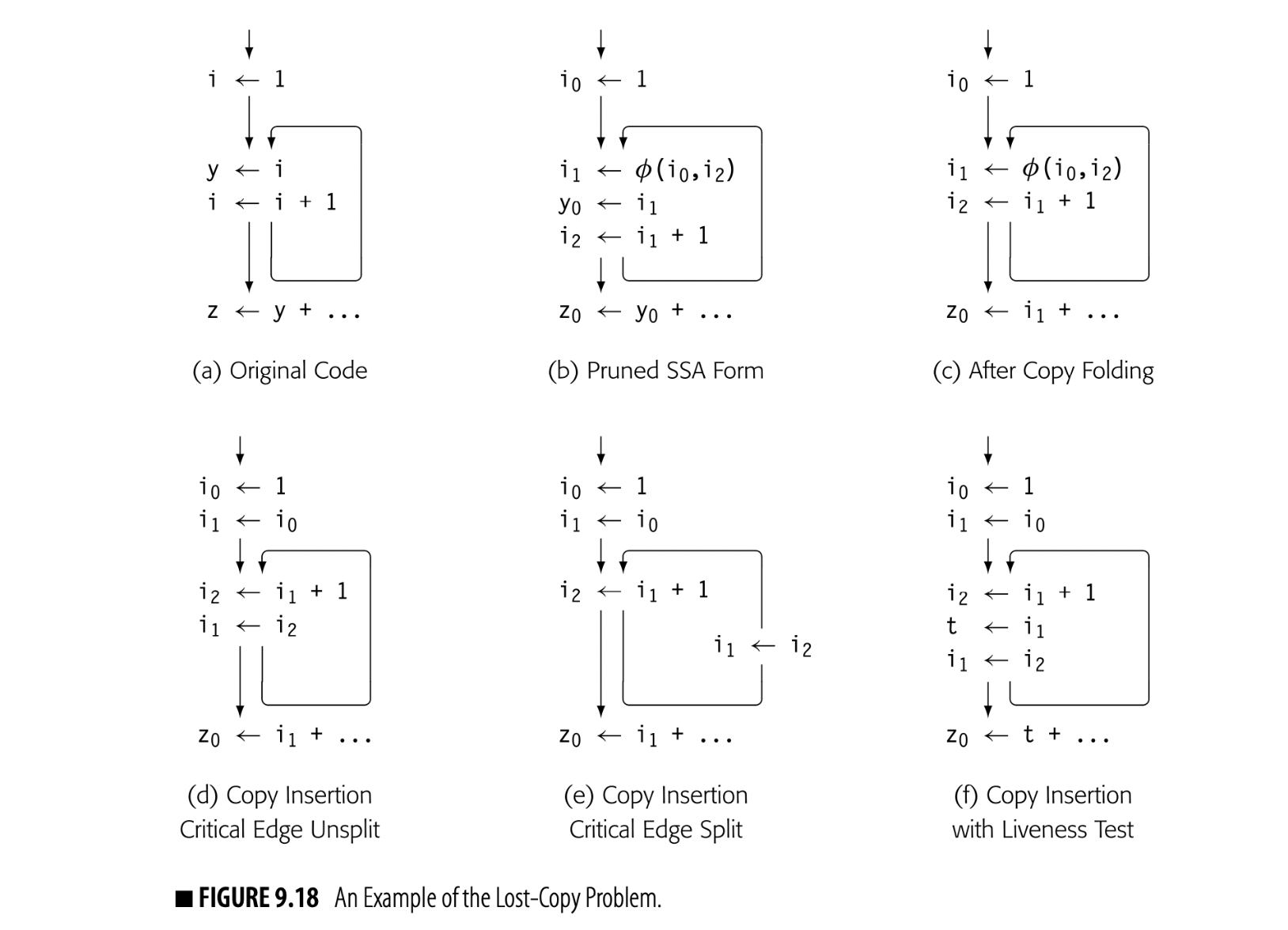

Fig. 9.18(a) shows an example to demonstrate the problem. The loop increments . The computation of after the loop uses the second-to-last value of . Panel (b) shows the pruned SSA for the code.

Panel (c) shows the code after copy folding. The use of in the computation of has been replaced with a use of . The last use of in panel (b) was in the assignment to ; folding the copy extends the live range of beyond the end of the loop in panel (c).

Copy folding an optimization that removes unneeded copy operations by renaming the source and destination to the same name, when such renaming does not change the flow of values is also called (see Section 13.4.3).

Copy insertion on the code in panel (c) adds to the end of the preloop block, and at the end of the loop. Unfortunately, that latter assignment kills the value in ; the computation of now receives the final value of rather than its penultimate value. Copy insertion produces incorrect code because it extends 's live range.

Splitting the critical edge cures the problem, as shown in panel (e); the copy does not execute on the loop's final iteration. When the compiler cannot split that edge, it must add a new name to preserve the value of , as shown in panel (f). A simple, ad-hoc addition to the copy insertion process can avoid the lost-copy problem. As the compiler inserts copies, it should check whether or not the target of the new copy is live at the insertion point. If the target is live, the compiler must introduce a new name, copy the live value into it, and propagate that name to the uses after the insertion point.

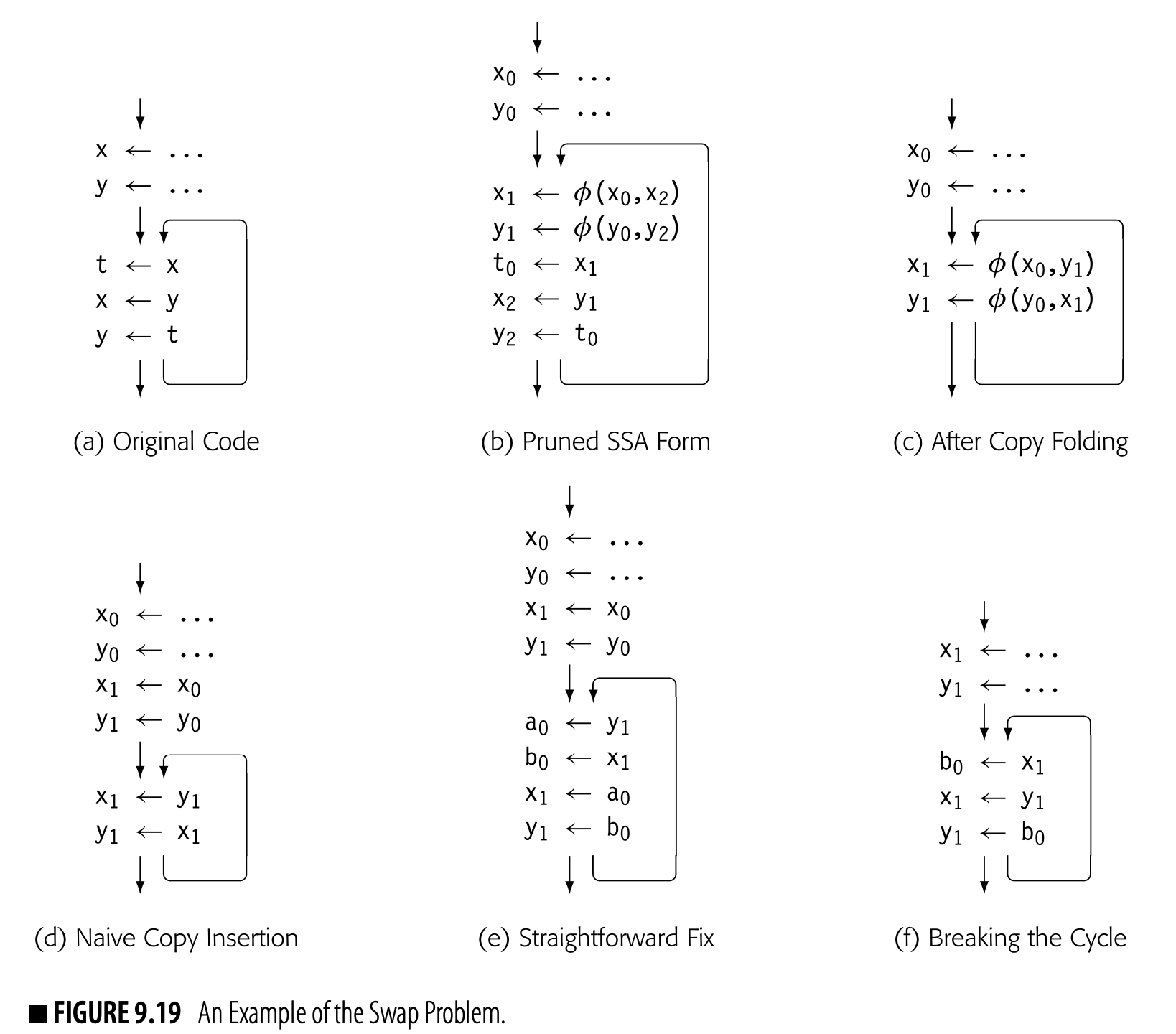

The Swap Problem

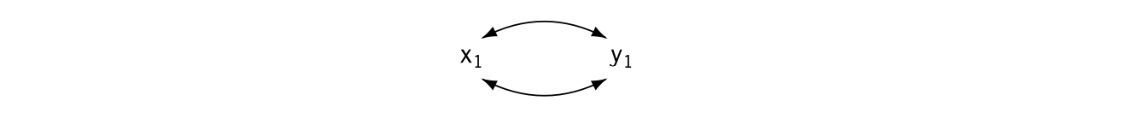

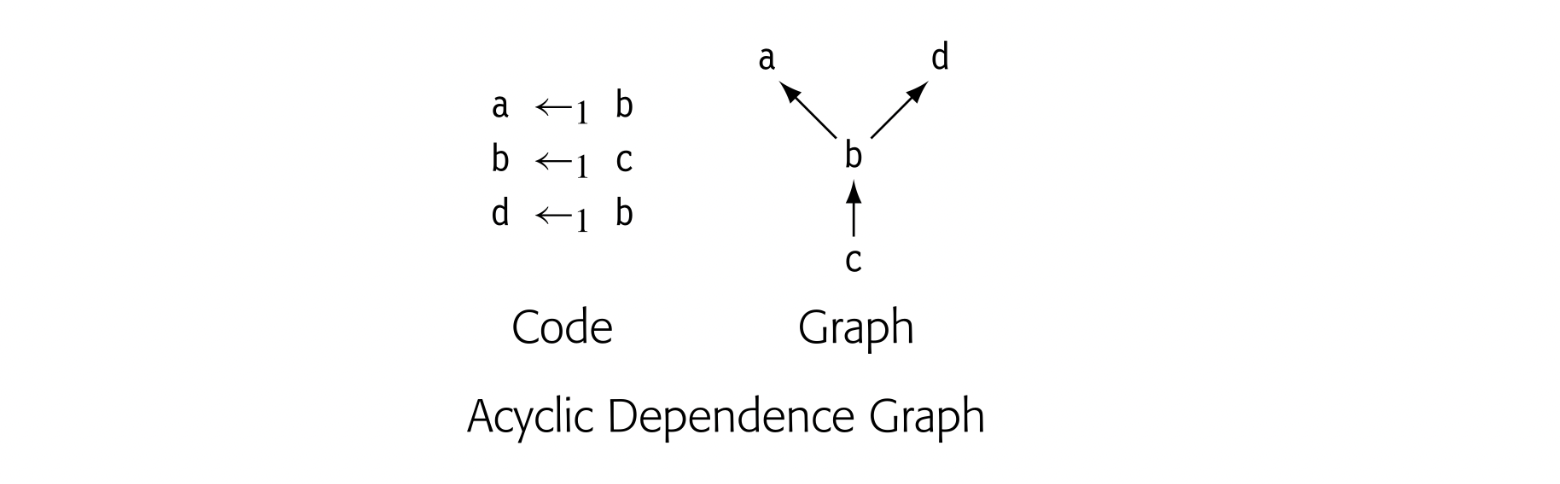

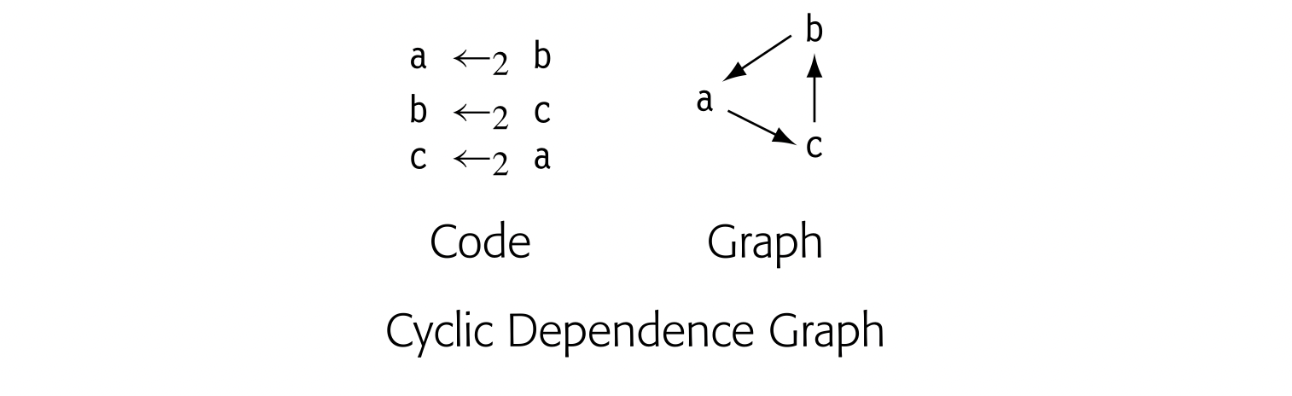

The concurrent semantics of -functions create another problem for out-of-SSA translation, which we call the swap problem. The motivating example appears in Fig. 9.19(a): a simple loop that repeatedly swaps the values of and . If the compiler builds pruned SSA-form, as in panel (b), and performs copy folding, as in panel (c), it creates a valid program in SSA form that relies directly on the concurrent semantics of the -functions in a single block.